No one denies that Al Padilla was a tough football coach. With his blunt features, thick black hair, he had the look. Stalking the field, grumbling and hollering, he made his teams repeat the same drills over and over until they got it right. People still tell the story of the lineman who dared to talk back.

“Coach called me over and told me to take my helmet off,” J. Jon Bruno recalls all these years later. “Whap! He hit me on the side of the head with his clipboard.”

Hit him so hard the clipboard broke. The next morning, Bruno showed up at Padilla’s office with a new one.

“It was my fault,” he says. “I could never be mad at him.”

Over the course of four decades, Padilla became an institution in East L.A., teaching the game to generations of young men at Roosevelt High and then rival Garfield High before moving to East L.A. College, where he led the Huskies to their first state championship.

Football was only part of Padilla’s impact on the community. Long after players graduated, they would get a phone call or a note from their old coach, who was checking up on them. If someone needed a job, he asked around. If someone died, he rounded up teammates to serve as pallbearers.

“Al could be a tough guy,” says Mike Garrett, who played for Padilla at Roosevelt before winning the Heisman Trophy at USC and playing in two Pro Bowls and a Super Bowl with the Kansas City Chiefs. “But off the field, he loved you to death.”

When Padilla died at age 90 earlier this month, word spread quickly. His former players commiserated. Some cried, including Bruno, who grew up to become bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Los Angeles. “I shouldn’t break down in tears,” Bruno says, “but he was one of the greatest mentors of my life.”

::

Plenty of good players, such as Garrett, have passed through Roosevelt and Garfield over the years. But neither of the schools, situated about four miles apart, has ever been considered a football powerhouse.

They are, however, a big deal in the community.

As many as 20,000 people show up for their annual rivalry game, the East L.A. Classic, each fall. Families are defined by whom they root for, the Rough Riders or Bulldogs. And Padilla stood at the center of it all.

“I shouldn’t break down in tears, but he was one of the greatest mentors of my life.”

— J. Jon Bruno, former player

His coaching career began at Roosevelt in the mid-1950s. He then switched to Garfield — “Turncoat,” Garrett says, only half-jokingly — in the 1960s.

Former players remember his attention to detail, especially along the line of scrimmage, where he had played in high school and college. Practices were demanding, always harder than the games.

“Coach wanted perfection,” says Bill Gonzalez, a star running back at Garfield in the early 1960s. “He told us, ‘Get it right, get it right.’”

Told them in a voice they can never forget.

“Oh my God,” Gonzalez says, “you could hear him all over the dang school.”

The Garfield Bulldogs had suffered through disappointing years when Padilla took over. By his second season, they were leagues champions, but wins and losses don’t fully account for the coach’s legacy.

Padilla always left a crate of apples or oranges in the visitors’ locker room on game day and instructed his team to greet opponents during warmups. Off the field, he demanded good grades. If a player had trouble with schoolwork or anything else, teammates were expected to help.

“He taught us how important it was to maintain relationships,” Bruno says. “To care for each other.”

Fatherly is a term his former players often use. The man they continued to call “Coach” through their adult years was equal parts demanding and supportive, always watching over.

“Coach was raised without a dad,” Garrett says. “Did you know that?”

::

Hector Albert Padilla was born March 22, 1930, in Tucson, Ariz., to Manuel, who worked as a boilermaker for the Southern Pacific Railroad, and Concepcion, who was a seamstress.

Manuel also played semipro baseball — he was a catcher — and had just enough time to pass on his love of the sport to his only son. He died from illness at 42 when Al was still in grade school.

In 1939, the family moved to Los Angeles where Padilla distinguished himself as captain of the football team and a star pitcher at Roosevelt High. A semipro baseball team sponsored by Ornelas Market recruited him for the local barrio league, with games played at a Boyle Heights park.

“Each team brought one new ball to the game,” he told The Times in 2006. “You could call it a two-ball league — and the winning team got to keep both balls.”

Though Occidental College offered him an athletic scholarship, Padilla could not pass the English entrance exam. He reacted in the same way — Get it right — that he would later stress to players.

First came a stint in the Army, then two years at junior college. In 1950, he transferred to Occidental, where he became an all-conference guard on the Tigers’ offensive line. At 5 feet 9 and 185 pounds, pro football was out of the question; another type of sports career called to him.

“No, there weren’t many Latino coaches at all,” Gonzalez said, “but he was intending to do that.”

Roosevelt High gave him a start, running the junior varsity football team, and it wasn’t long before Padilla worked his way up the ladder. His son, Steve, the Column One editor at The Times, recalls him coming home with a hoarse voice. The coach wasn’t sick; he had been shouting at his players all afternoon.

“Were they screwing up?” Steve asked.

“No,” his father replied. “It was just time to yell at them.”

In this era, his style — especially the part where he breaks a clipboard over a player’s head — might not be acceptable , but Garrett suggests that Padilla be viewed in the context of his time.

“It was a throwback to World War II and the Korean War,” Garrett says. “His generation served in the military, then came back and taught the next generation with sternness, but also with compassion.”

::

Lynn Cain was done playing football.

After three seasons at USC and seven more in the NFL with the Atlanta Falcons and Los Angeles Rams, the running back decided to become a coach. His first job at an Atlanta high school led to a spot on the staff at Southwest Baptist University.

Arriving at the campus in a small Missouri town, he received a letter from Padilla.

“Wow,” he recalls thinking. “How did Al Padilla know I was in Missouri?”

A decade earlier, Cain had been a part of Padilla’s greatest success, that championship season at East L.A. College.

The Huskies weren’t much of a team when Padilla took over, stumbling to a 1-9 record the first season. Needing fresh blood, he scoured Southern California for talent that had been overlooked by larger schools. Five of the prospects he discovered — including Cain, Mike Davis and David Gray — eventually wound up in the NFL.

“Think of the guys he recruited,” Cain says. “It was like a Disney story.”

The 1974 squad flipped its record to 9-1-2, defeating San Jose City College in the Shrine Potato Bowl to claim the state title. Though the team soon scattered, some going to NCAA programs, others dropping out of football, Padilla added their names to a long list.

“He stayed connected with his players,” Cain said. “Always had some idea what you were doing in life.”

Padilla helped Cain get the head coaching job at East L.A. College in 2007. He found jobs for other former players outside of football, whether it was working in a factory or delivering meat.

This emphasis on relationships, on caring for one another, rubbed off on the men who played for him. They continued visiting Padilla and his wife, Dora, at their Alhambra home long after his retirement, after streaks of gray began to show in his black hair and that voice grew a little raspier, a little quieter.

In recent years, when he and Dora moved into an assisted living facility, his former players brought along kids and grandchildren to meet the old coach.

“Al Padilla was cradle to the grave,” Cain said. “When you joined his team, he had you cradle to grave.”

1/25

Kobe Bryant, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sean Connery and more. (Los Angeles Times)

2/25

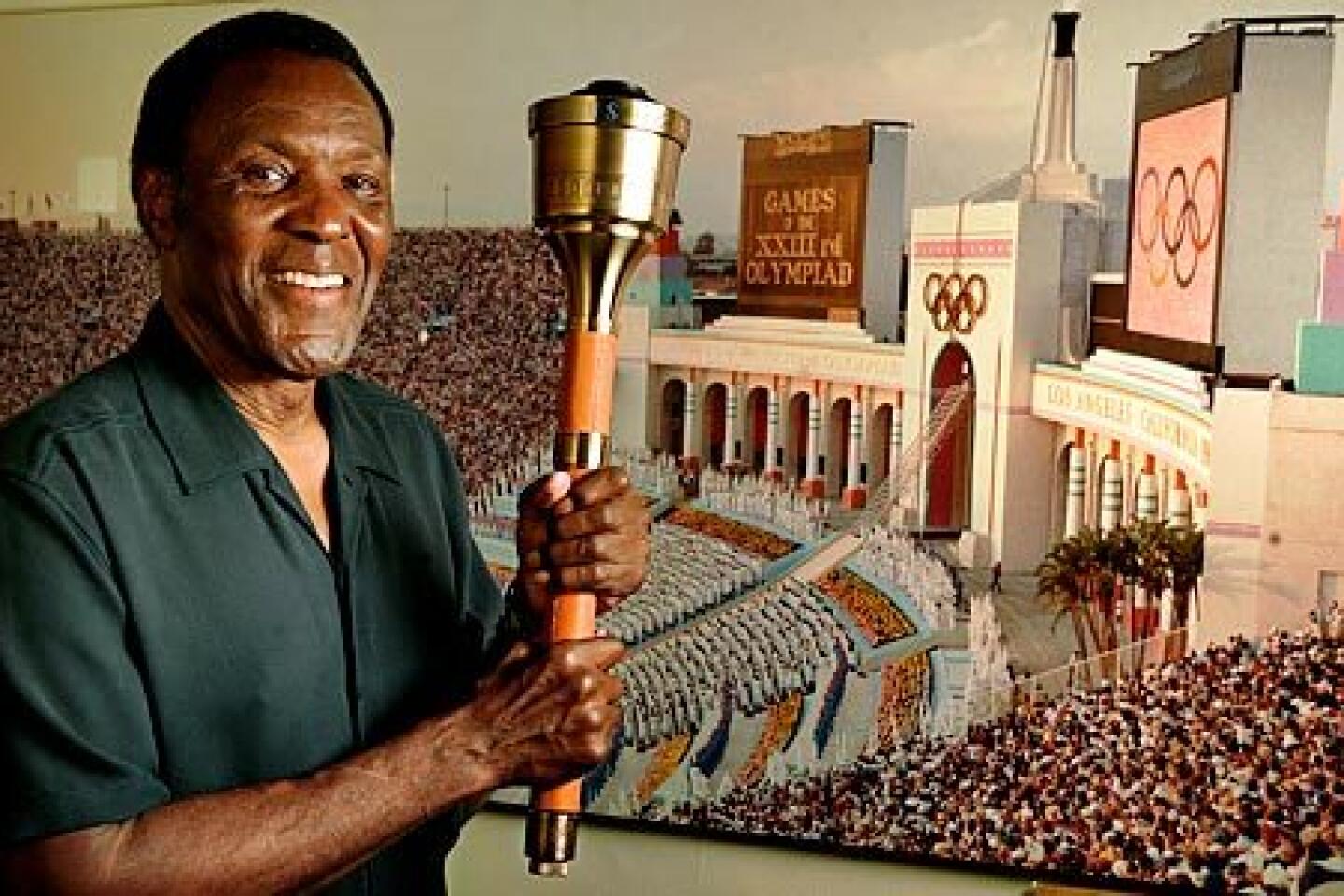

Rafer Johnson, winner of the 1960 Olympic decathlon gold medal, was a man whose legacy was interwoven with Los Angeles history, beginning with his performances as a world-class athlete at UCLA and punctuated by the night in 1968 when he helped disarm Robert F. Kennedy’s assassin at the Ambassador Hotel. Johnson lit the Olympic flame at the opening of the 1984 Summer Games in Los Angeles. He was 86.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times) 3/25

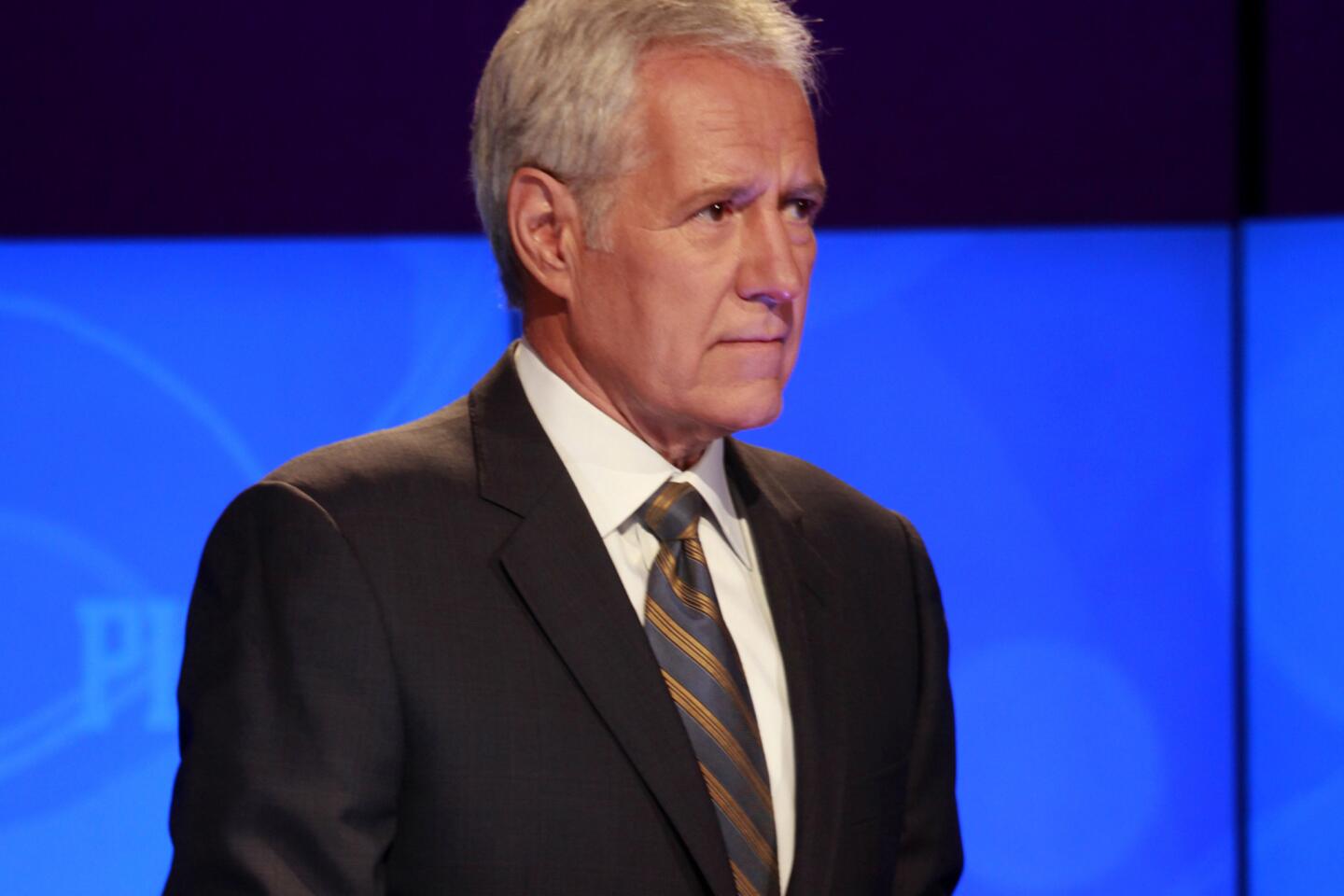

With his quick wit and easy smile,

Alex Trebek drove the game show “Jeopardy!” up the ratings charts and became a welcome television host in America’s living rooms. As the quiz show rolled through the decades, Trebek remained a comfortable fit — in a 2014 Reader’s Digest poll, Trebek ranked as the eighth-most trusted person in the United States, right behind Bill Gates and 51 spots above Oprah Winfrey. He was 80.

(Los Angeles Times) 4/25

Guitarist Eddie Van Halen’s speed and innovations along the fretboard inspired a generation of imitators as the band bearing his name rose to MTV stardom and multiplatinum sales over 10 consecutive albums. The streak made Van Halen one of the most successful bands in rock history, including two albums that reached diamond status (10 million copies sold): 1978’s debut “Van Halen” and 1984’s “1984.” He was 65.

(Wibbitz/Getty) 5/25

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg championed women’s rights — first as a trailblazing civil rights attorney who methodically chipped away at discriminatory practices, then as the second woman to serve on the Supreme Court, and finally as an unlikely pop culture icon. A feminist hero dubbed Notorious RBG, Ginsburg became the leading voice of the court’s liberal wing, best known for her stinging dissents on a bench that mostly skewed right since her 1993 appointment. She was 87.

(Kiichiro Sato / Associated Press) 6/25

Chadwick Boseman’s breakout role was playing Dodger Jackie Robinson in the 2013 sports biopic “42.” The next year, he made an electrifying lead turn as James Brown, the Godfather of Soul, in “Get on Up.” Then came the role that would change his career: As

Black Panther, the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s first Black superhero, Boseman became the face of Wakanda to millions of fans around the world and helped usher in a new and inclusive era of superhero blockbusters. He was 43.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 7/25

Sumner Redstone outmaneuvered rivals to assemble one of America’s leading entertainment companies, now called ViacomCBS, which boasts CBS, Comedy Central, MTV, Nickelodeon, BET, Showtime, the Simon & Schuster book publisher and Paramount Pictures movie studio. Unlike contemporaries Rupert Murdoch and Ted Turner, Redstone was not a visionary, but rather a hard-charging lawyer and deal maker who pursued power and wealth through the accumulation of content companies. He was 97.

(Brian Vander Brug / Los Angeles Times) 8/25

Regis Philbin reigned for decades as the comfortable and sometimes cantankerous morning host of “Live,” first with Kathie Lee Gifford and later Kelly Ripa, above. He earned Emmy nominations by the armful, hosted New Year’s Eve specials, rode in parades, set a record for the most face-time hours on television and helped reinvigorate prime-time game shows with “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire.” He was 88.

(Charles Sykes / Associated Press) 9/25

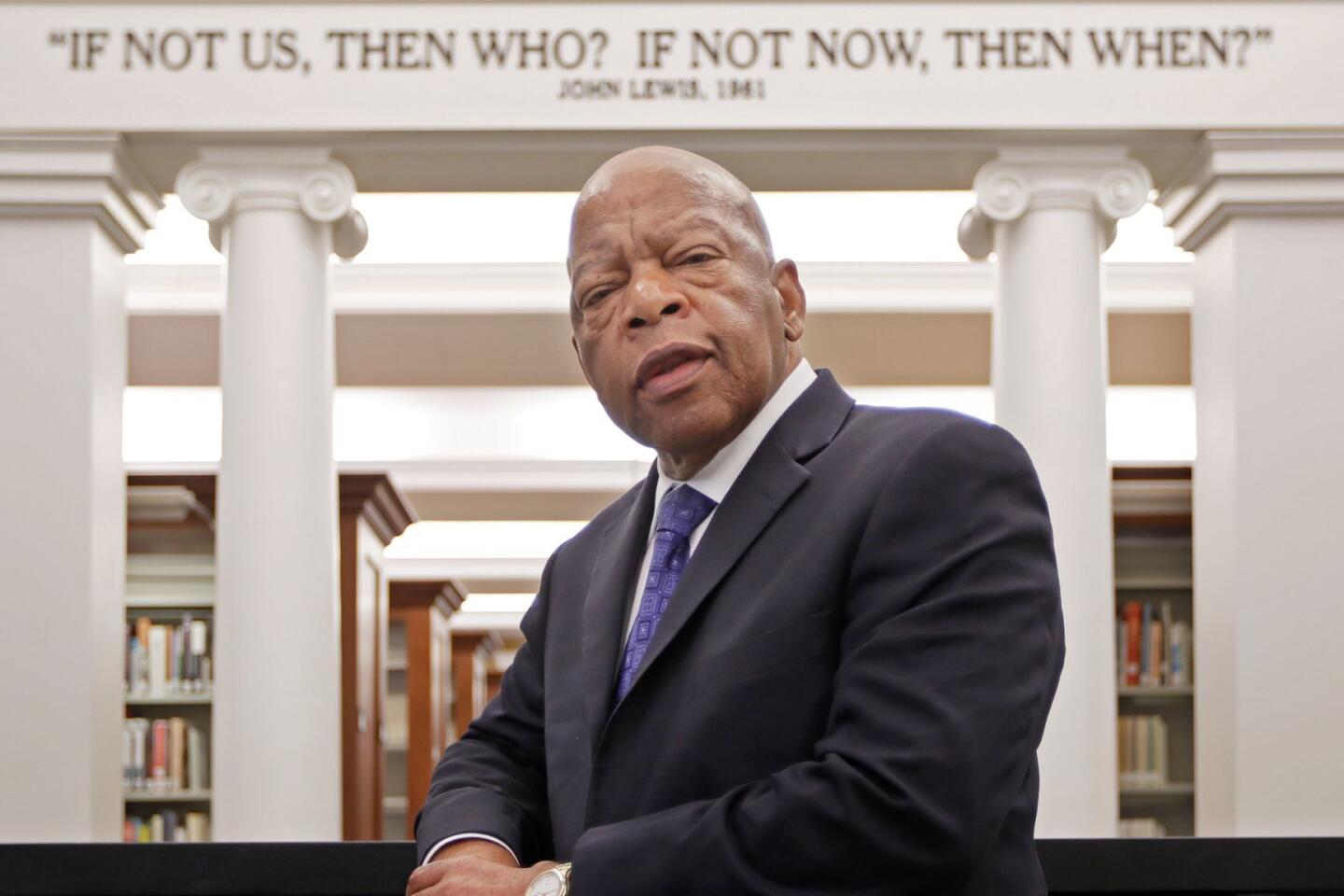

Rep. John Lewis famously shed his blood at the foot of a Selma, Ala., bridge in a 1965 demonstration for Black voting rights, and went on to become a 17-term Democratic member of Congress. An inspirational figure for decades, Lewis was one of the last survivors among members of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s inner circle. He was 80.

(Mark Humphrey / Associated Press) 10/25

Country music firebrand and fiddler Charlie Daniels started out as a session musician, which included playing on Bob Dylan’s 1969 album “Nashville Skyline,” and beginning in the early 1970s toured endlessly with his own band, sometimes doing 250 shows a year. In 1979, Daniels had a crossover smash with “The Devil Went Down to Georgia,” which topped the country chart, hit No. 3 on the pop chart and was voted single of the year by the Country Music Assn. He was 83.

(Rick Diamond / Getty Images for IEBA) 11/25

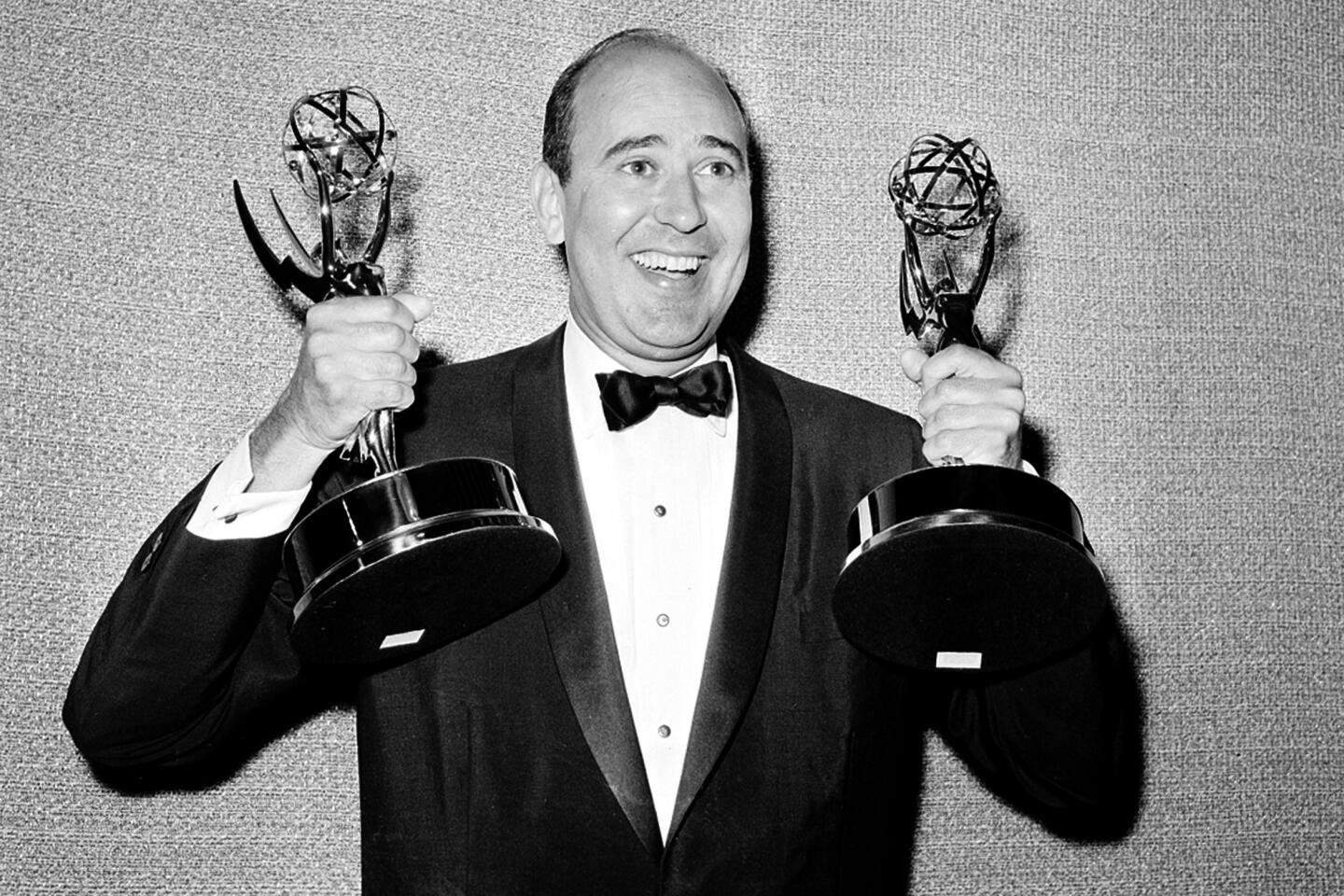

Carl Reiner first came to national attention in the 1950s on Sid Caesar’s “Your Show of Shows,” where he wrote alongside Mel Brooks, Neil Simon and other comedy legends. He later created “The Dick Van Dyke Show,” one of TV’s most fondly remembered sitcoms, and directed hit films including “The Comic” (1969), starring Van Dyke; “Where’s Poppa?” (1970), starring George Segal and Ruth Gordon; “Oh, God!” starring George Burns and John Denver; and four films starring Steve Martin. He was 98.

(Associated Press ) 12/25

The flamboyant, piano-pounding Little Richard roared into the rock ‘n’ roll spotlight in the 1950s with hits such as “Tutti-Frutti,” “Long Tall Sally” and “Good Golly, Miss Molly.” The Georgia native’s raucous sound fused gospel

fervor and R&B sexuality, profoundly influencing the Beatles, James Brown (who succeeded him in one of his early bands), Jimi Hendrix (one of his backup musicians in the mid-’60s) and Bruce Springsteen. He was 87.

(Boris Yaro / Los Angeles Times) 13/25

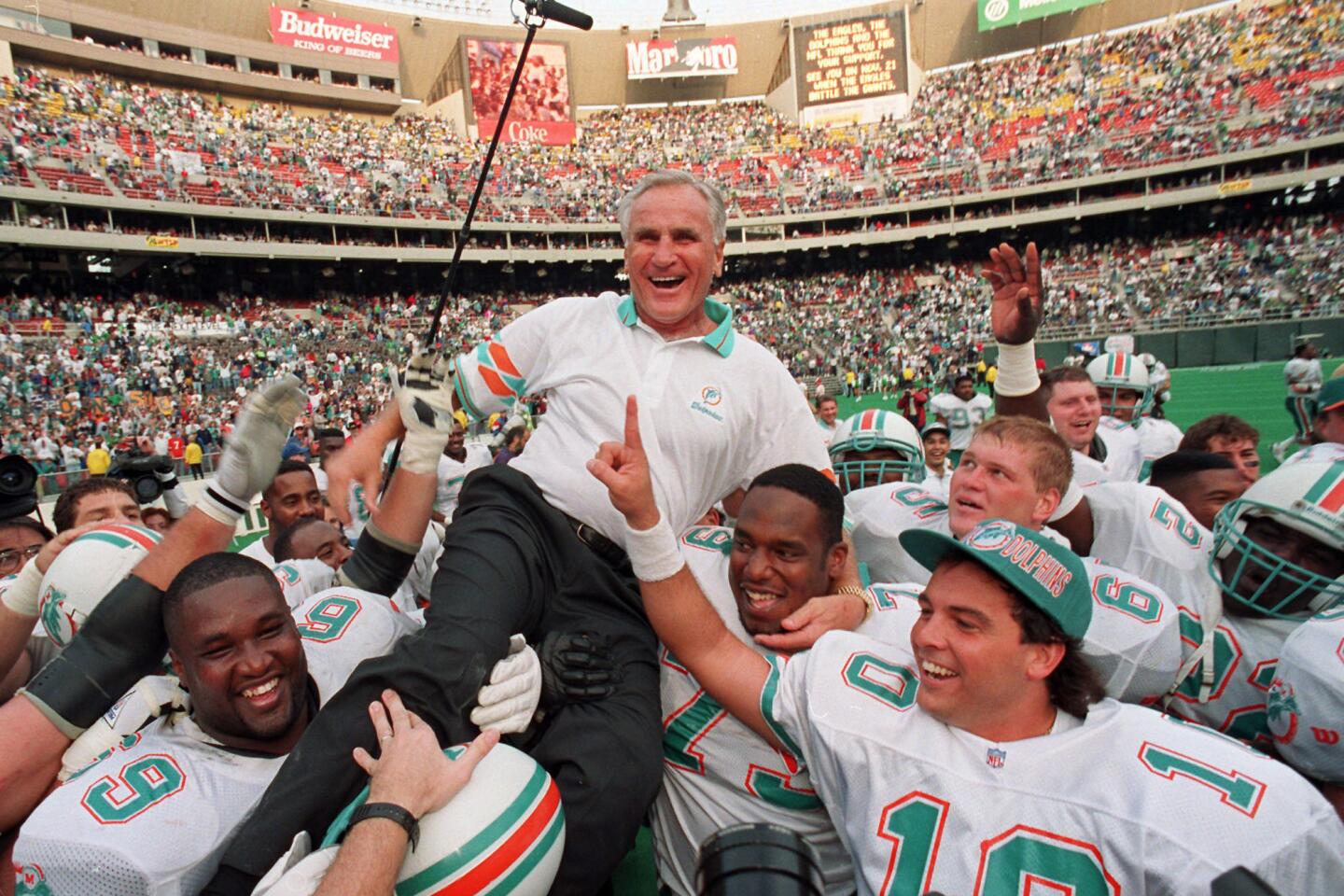

Don Shula was the NFL’s winningest coach, leading the 1972 Miami Dolphins to the league’s only undefeated season. He coached the Baltimore Colts to one Super Bowl and the Dolphins to five, winning Lombardi Trophies after the 1972 and ’73 seasons. He was 90.

(ASSOCIATED PRESS) 14/25

Former Egyptian

President Hosni Mubarak crushed dissent for decades until the 2011 Arab Spring movement drove him from power. During his presidency, which spanned nearly 30 years, he protected Egypt’s stability as intifadas roiled Israel and the Palestinian territories, the U.S. led two wars against Iraq, Iran fomented militant Shiite Islam across the region and global terrorism complicated the divide between East and West. He was 91.

(Sameh Sherif / AFP/Getty Images) 15/25

Among his 40-odd films,

burly Brian Dennehy played a sheriff who jailed Rambo in “First Blood,” a serial killer in “To Catch a Killer” and a corrupt sheriff in “Silverado.” On Broadway, he was awarded Tonys for his roles in “Death of a Salesman” (1999) and “Long Day’s Journey Into Night” (2003). He was 81.

(Dia Dipasupil) 16/25

Singer-songwriter John Prine broke onto the folk scene in 1971 with a self-titled album that included two songs brought to broader audiences by Bette Midler and Bonnie Raitt: “Hello in There” and “Angel From Montgomery,” respectively. In 2019, he was elected to the Songwriters Hall of Fame. He was 73.

(Frazer Harrison / Getty Images for Stagecoach) 17/25

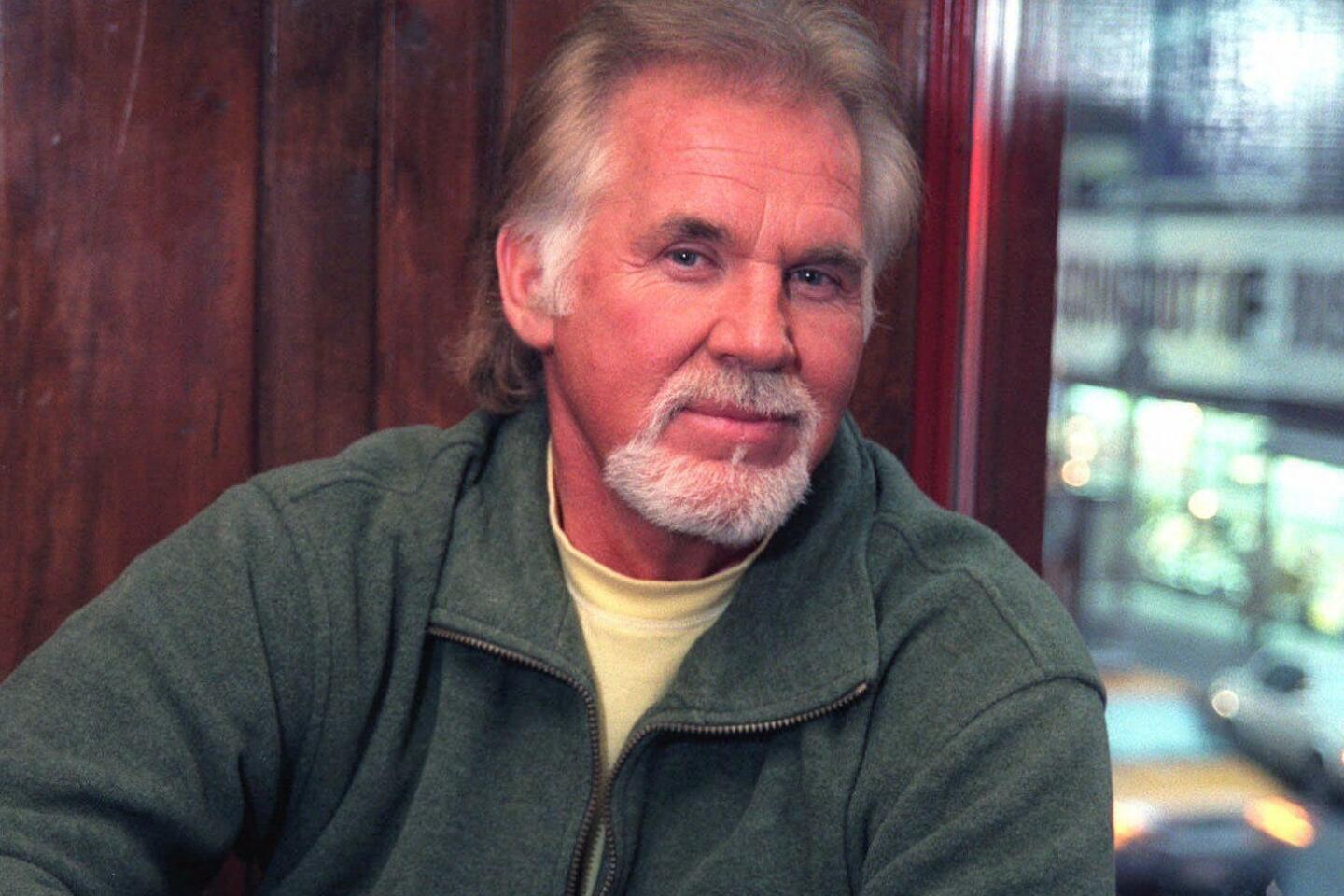

Country singer Kenny Rogers racked up an impressive string of hits — initially as a member of The First Edition starting in the late 1960s and later as a solo artist and duet partner with Dolly Parton — and earned three Grammy Awards, 19 nominations and a slew of accolades from country-music awards shows. Country purists balked at his syrupy ballads, but his fans packed arenas that only the titans of rock could fill. He was 81.

(Suzanne Mapes / Associated Press) 18/25

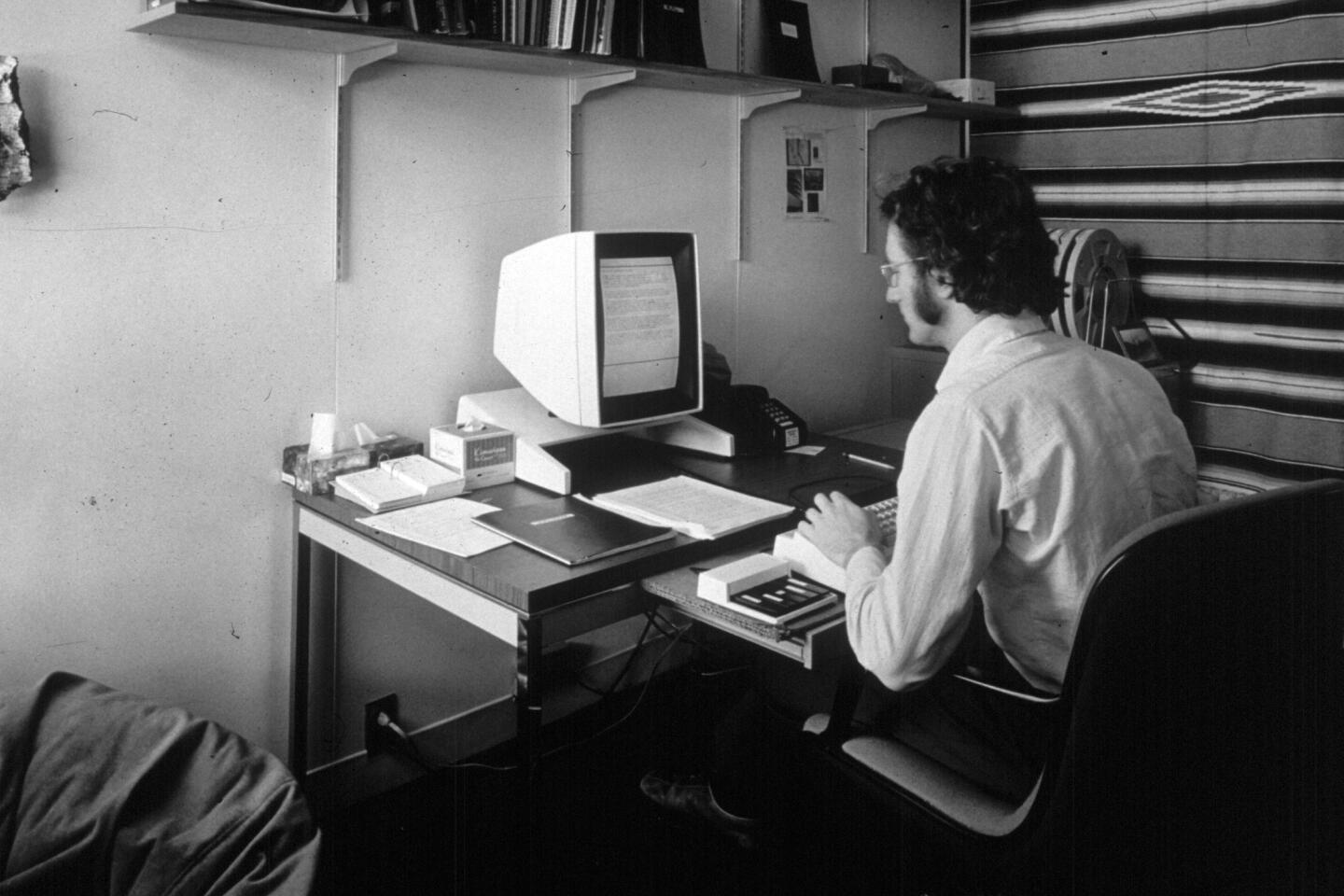

Xerox researcher Larry Tesler pioneered concepts that made computers more user-friendly, including moving text through cut, copy and paste. In 1980, he joined Apple, where he worked on the Lisa computer, the Newton personal digital assistant and the Macintosh. He was 74.

(AP) 19/25

Ski industry pioneer Dave McCoy transformed a remote Sierra peak into the storied Mammoth Mountain Ski Area. Over six decades, it grew from a downhill depot for friends to a profitable operation of 3,000 workers and 4,000 acres of ski trails and lifts, a mecca for generations of skiers and boarders. He was 104. (Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

20/25

Screen icon

Kirk Douglas brought a clenched-jawed intensity to an array of heroes and heels, receiving Oscar nominations for his performances as an opportunistic movie mogul in the 1952 drama “The Bad and the Beautiful” and as Vincent van Gogh in the 1956 drama “Lust for Life.” As executive producer of “Spartacus,” Douglas helped end the Hollywood blacklist by giving writer Dalton Trumbo screen credit under his own name. He was 103.

(Annie Wells / Los Angeles Times) 21/25

“Queen of Suspense”

Mary Higgins Clark became a perennial best-seller, writing or co-writing “A Stranger Is Watching,” “Daddy’s Little Girl” and more than 50 other favorites. Her sales topped 100 million copies, and many of her books, including “A Stranger is Watching” and “Lucky Day,” were adapted for movies and television. She was 92.

(Associated Press) 22/25

Fred Silverman was the head of programming at CBS, where he championed a string of hits including “The Mary Tyler Moore Show,” “All in the Family,” “MASH” and “The Jeffersons.” Later at ABC, he programmed “Laverne & Shirley,” “The Love Boat,” “Happy Days” and the 12-hour epic saga “Roots.” He was 82.

(Associated Press) 23/25

Former California

Rep. Fortney “Pete” Stark Jr. represented the East Bay in Congress for 40 years. The influential Democrat helped craft the Affordable Care Act, the signature healthcare achievement of the Obama administration, and also created the 1986 law best known as COBRA, which allows workers to stay on their employer’s health insurance plan after they leave a job. He was 88.

(Associated Press) 24/25

News anchor

Jim Lehrer appeared 12 times as a presidential debate moderator and helped build “PBS NewsHour” into an authoritative voice of public broadcasting. The program, first called “The Robert MacNeil Report” and then “The MacNeil-Lehrer Report,” became the nation’s first one-hour TV news broadcast in 1983. Lehrer was 85.

(David McNew / Getty Images) 25/25

Terry Jones was a founding member of the Monty Python troupe who wrote and performed for their early ’70s TV series and films including “Monty Python and the Holy Grail” in 1975 and “Monty Python’s Life of Brian” in 1979. After the Pythons largely disbanded in the 1980s, Jones wrote books on medieval and ancient history, presented documentaries, wrote poetry and directed films. He was 77.

(Associated Press)