Monument Valley: A stark beauty deep in Navajo country

Commanding buttes and mesas plus a complicated history mark the spectacular Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park.

Zane Grey knew how to make an entrance, or at least how to describe one. As the famous Western writer liked to tell the story, he was on horseback in 1913, riding deep into Navajo country, when a flash lighted up the desert. That flash, Grey wrote, "revealed a vast valley, a strange world of colossal shafts and buttes of rock, magnificently sculptured, standing isolated and aloof, dark, weird, lonely."

Grey had found his way to Monument Valley, before John Ford and John Wayne showed up to make "Stagecoach" and before all those other makers of movies and television and marketers of cars and cigarettes made the buttes a symbol of the Wild West. Even if you suspect poetic license in the timing of that lightning bolt, the man saw the valley raw.

Thinking of him last month, I rose before sunrise in a hotel on the Arizona-Utah border, drove to a parking lot and hiked down Wildcat Trail into the heart of Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park. Mark Boster, the photographer who has been revisiting Western icons with me the last several months, had set up on high ground, so I was alone.

There was a scent of wet sage, almost no sound but the wind. Then the sun rose, the mesas blazed and dead ahead, the towering West Mitten Butte jumped from pre-dawn obscurity into silhouette.

It was tremendous. Only for a moment did I wonder if this was where Chevy Chase crashed the Griswold family station wagon in "National Lampoon's Vacation."

Monument Valley is part of the Navajo Nation reservation, a 640-mile drive from Los Angeles, 175 miles northeast of Flagstaff, Ariz., about 25 miles north of the sleepy town of Kayenta. The valley's most famous mesas, buttes and spires stand within the boundaries of the tribal park. And you, my fellow Americans, should go to see them.

Why? Because it's embarrassing to stand in the middle of such stark beauty and realize that most of the other tourists are speaking French, German, Italian, Japanese or Chinese.

You should know, however, that this is no national park. Instead of the National Park Service infrastructure, you will find a 17-mile dirt road looping around the valley's most admired landmarks, a dozen or more jewelry and souvenir stands, two hotels in the immediate neighborhood, and no alcohol on their menus.

To leave the loop road, you must hire a Navajo guide. You may notice a weather-beaten trailer, perhaps neighbored by a rounded earthen mound. These are private homes and traditional hogans, without electricity or running water, that house a handful of Navajo families that date back here for generations. Many of them make their living from tourists, but most don't want a paved road inside the park because then too many would come.

And then there's the uranium. From the 1940s to the 1960s, with the approval of U.S. and Navajo leaders, mining companies extracted tons of ore here to fuel U.S. nuclear programs. Then they abandoned the sites, including Skyline Mine on the valley's Oljato Mesa. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency found lingering elevated radiation at Skyline and in 2011 completed an $8-million cleanup, but elsewhere in Navajo country hundreds of abandoned mines await remediation. A tourist might see none of this, but locals know all about it.

So the valley is complicated. But it's also plainly spectacular, beginning with the approach up U.S. Highway 163. You snap to attention at the sight of angular Agathla, a.k.a. El Capitan, first of the buttes, looming like a stairway to the stratosphere. Soon after comes Sentinel Mesa, a sort of Greek Acropolis, if the Acropolis were swaddled in orange by Christo.

Most tourists stay a day or two. We stayed four, circled the valley alone and with a guide, under blue skies and gray. We paid respects to Rain God Mesa, the Thumb, Gray Whiskers, the Hub and the Cube; ate enough fry bread to last a lifetime; and stood among the tripod people at sunset, lining up the Mitten buttes with the same boulders that Ansel Adams used in 1950.

Then one afternoon, a roar filled the valley and the clouds burst. Monsoon.

Within minutes, Spearhead Mesa had five waterfalls coursing down its face. Sentinel Mesa wore a crown of dark clouds. In the storm, the landscape seemed doubly alive, reds and greens literally saturated, sky riven by lightning, puddles and streams threatening the road. We sprinted for the car and rushed away, scared and thrilled.

We stayed one night in the View Hotel, earth-toned, low-slung, handsome on the valley-facing side and homely on the other. It was built in 2008 by the Navajo tribe, and every room has a balcony that looks out on a classic panorama.

A puddle left by a passing storm reflects the buttes in Monument Valley. ( Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times ) More photos

Then we moved to Goulding's Lodge, five miles outside the park. It was Harry Goulding (with his wife, Leone "Mike" Goulding) who started a trading post here in the 1920s, and it was Goulding who traveled to Hollywood in 1938 and persuaded Ford to come and shoot "Stagecoach."

The Gouldings ran their desert outpost for decades, tending to filmmakers, peddling curios, steadily adding rooms and services. Spend a few minutes among the old photos and movie posters in its little museum and you'll see the old guest register in which John Wayne wrote: "Harry, you and I both owe these monuments a lot."

Check the new guest register and you find that of the last 115 guests who arrived before Aug. 26, 76 were from abroad. Are Americans outnumbered because we'd rather wait for cooler weather? Because Europeans are more curious about Native American culture than we?

I don't know. I tried asking a few Navajo, but we always ended up veering to another subject.

Ned Black, 44, paused at his jewelry stand to tell me he tries to be happy all day, but "it's hard to be happy all day. You don't know who you're going to come across."

Charles Phillips, a 36-year-old guide, stopped for provisions before carrying us off on a demanding four-hour off-road exploration in a battered Chevy Suburban: "I'm gonna get me a drink before we go. Gonna get me a Budweiser," he said, a twinkle in his eye, testing us.

A minute later he was back with a Powerade. (Phillips was working with two broken ribs, because the week before a horse had thrown him onto a rock. Laughing hurt, but he still wanted to.)

I was ready for more sly wit from Linda Jackson, who operates the cafe trailer at John Ford's Point. "Sarcasm. One of the free services I offer," said a sign next to the counter. But Jackson instead told us a heartfelt story about the day her 32-year-old son, Ericson Cly, died.

He was struck by lightning, she told us. Right here at John Ford's Point. On an August day in 2006.

We told her how sorry we were, looked at the dirt, looked at the sky, looked at the memorial marker that stands nearby. Then we made another loop through all that harsh beauty.

Timeline: Wind, water, migration, movies

Nature and people carve a lasting impression on Monument Valley.

About 50 million years ago: Wind and water start shaping Monument Valley, eventually causing sandstone monoliths to emerge.

Before 1400: The Anasazi occupy Monument Valley, along with other corners of the Southwest, and build many cliff dwellings and food-storage sites. Then they vanish.

After 1400: The Dine (pronounced Di-Nay) take up residence in and around Monument Valley. Other native tribes take to calling them the Navajo, as do the Spanish and then the Americans, marching westward.

1863: Eager to take their land, the U.S. government orders the relocation of all Navajos to a reservation at Ft. Sumner in Bosque Redondo, N.M. Enforcing the order, Col. Kit Carson passes through Monument Valley but fails to capture chief Hush-Kaaney (a.k.a. Hoskaninni), who remains a leader in the area for decades.

1868:A larger Navajo reservation is established, and an 1884 expansion includes Monument Valley. Eventually the reservation, also known as the Navajo Nation, includes about 27,000 square miles of Arizona, Utah and New Mexico.

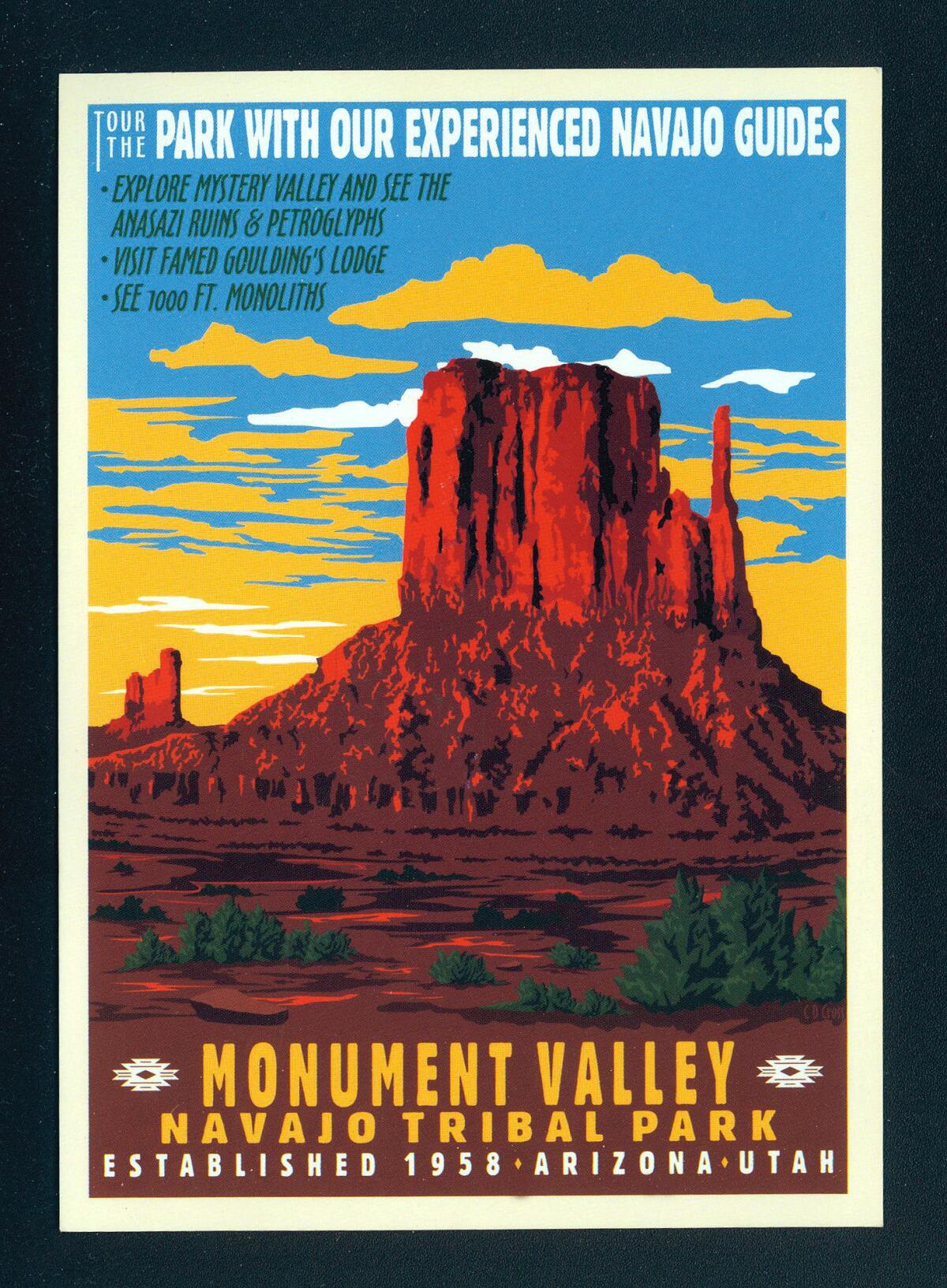

A present-day photograph of Monument Valley contrasted with the postcard "Sunset on West Mitten Butte" from Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park. (Photograph: Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times. Postcard: C.D. Cross / Retro Ranger Graphics.)

1913: Author and sportsman Zane Grey arrives in the valley as a storm is approaching. In 1922's "Tales of Lonely Trails," Grey writes that his first view "came with a flash of lightning. It revealed a vast valley, a strange world of colossal shafts and buttes of rock, magnificently sculptured, standing isolated and aloof, dark, weird, lonely."

1925: Harry Goulding and his wife, Leone (nicknamed Mike), establish a trading post on a view location near the northwest rim of the valley. The same year, director George B. Seitz brings a film crew to the valley to make the silent black-and-white feature "The Vanishing American." Based on a Zane Grey novel, the movie comes and goes.

1938: Eager to bring money to the Depression-ravaged valley, Harry Goulding goes to Hollywood bearing photos of Monument Valley and bluffs his way into a meeting with famed director John Ford. Soon after, Ford's cast and crew arrive in the valley to make "Stagecoach."

1939: "Stagecoach" revives the western genre, gives Ford's career a new direction and makes John Wayne a star. Ford goes on to make numerous movies in the valley, including "My Darling Clementine" (1946), "Fort Apache" with Wayne (1948) and "She Wore a Yellow Ribbon," also with Wayne, (1949).

Early 1940s: Uranium mining begins on Oljato Mesa at the western edge of the valley and continues into the 1960s, leaving a legacy of elevated radiation, pollution and controversy.

1953: Goulding's Lodge expands to include a motel.

1956: Release of Ford's "The Searchers," shot in the valley with Wayne. (In 2008, the American Film Institute named "The Searchers" the best western ever.)

1958: The Navajo Tribal Council establishes Monument Valley as a tribal park.

1960: Release of Ford's "Sergeant Rutledge," shot in the valley.

1963: Nearing 70, John Ford releases his last Monument Valley movie, "Cheyenne Spring." The Gouldings sell their lodge to a college, which later sells it to its current owners, the LaFont family.

1969: Peter Fonda leads the cast and crew of "Easy Rider" through the valley.

1975: Clint Eastwood directs and stars in "The Eiger Sanction," using Monument Valley's Totem Pole formation in rock-climbing scenes.

1983: In "National Lampoon's Vacation," Chevy Chase crashes the family station wagon in the valley.

1990: Traveling through time in "Back to the Future III," Michael J. Fox finds himself crossing the valley in a silver DeLorean.

1991: With the law in hot pursuit, Geena Davis and Susan Sarandon race through the valley in "Thelma & Louise."

2000: PBS airs "The Return of Navajo Boy," a documentary that ties a Monument Valley family's health problems to nearby uranium mining.

2008: The View Hotel, a round fireplace dominating its two-story lobby, opens, the first hotel inside the tribal park. It's owned by the Navajo tribe and managed by a Navajo family. Goulding's has grown into a compound that includes a trading post, hotel, restaurant, campground and museum, with vacation-rental apartments nearby.

2011: An $8-million Environmental Protection Agency clean-up is completed at the Skyline Mine, a former uranium mine on Oljato Mesa, less than 2 miles from Goulding's Lodge.

2012: Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park, now 91,696 acres, reports 422,932 visitors.

2013: Johnny Depp, playing Tonto in a remake of "The Lone Ranger," sits astride a white horse with co-star Armie Hammer at John Ford's Point in the valley.

Sources: "Land of Room Enough and Time Enough: The Story of Monument Valley," by Richard E. Klinck; "The Secrets of Monument Valley," by Tony Perrottet; https://www.imdb.com; https://www.gouldings.com; https://www.monumentvalleyview.com; https://www.navajonationparks.org; https://www.historytogo.utah.gov; Arizona Geological Survey repository and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Arizona: Page is the gateway to photographers' dreams

Antelope Canyon and Horseshoe Bend are dramatic subjects for photographers. Curving sandstone, filtered light and vivid sky prove majestic. Take a tripod.

At Horseshoe Bend the Colorado River makes a 270-degree curve. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times) More photos

Monument Valley is great place for a photographer to look up. Antelope Canyon and Horseshoe Bend, 125 miles to the west, are great places to look down.

The canyon and the bend — a narrow slot canyon and a deep, broad stretch of the Colorado River — are at the edge of Page, Ariz., a tourist town that serves as a jumping-off point for houseboats and watersports at Lake Powell.

To visit Horseshoe Bend, where the deep green Colorado River suddenly turns 270 degrees at the bottom of a big red gorge, you drive 4 miles south of Glen Canyon Dam on U.S. 89. Park and walk 3/4 of a mile over a scrub-brush hill to the edge of a cliff.

Be careful — there are no guardrails or fences. And be glad: It's free, and the view of the twisting river is jaw-dropping. At sunrise or sunset, the play of land, water, light and shadow is doubly dramatic and challenging for a photographer seeking that perfect exposure. For more information, go to https://www.horseshoebend.com.

Navajo guide Raymond Chee stands in the opening to Antelope Canyon near Page, Ariz. The canyon, part of Lake Powell Navajo Tribal Park, is carved in large part by monsoon runoff and is up to 120 feet deep with just a ribbon of blue sky above. ( Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times ) More photos

Upper Antelope Canyon, which is part of Lake Powell Navajo Tribal Park, is carved in large part by monsoon runoff and is up to 120 feet deep with just a ribbon of blue sky above. The filtered light, rich colors and varied textures of the crevasse's sandstone walls create remarkable effects — one moment, frozen flames; the next, stretching taffy.

You can't enter without a guide, and you can't enter at all if a lot of rain is expected upstream. (A 1997 flash flood in Lower Antelope Canyon killed 11 tourists. The week before our Aug. 29 visit, monsoons closed the area for two days and added several feet of silt to the canyon floor.) Since 2011, Navajo leaders have imposed a two-hour limit per canyon on all visitors. Depending on which of several permit-bearing guide companies you sign up with, guides can also take you to longer, narrower Lower Antelope Canyon and other areas.

Fifty-minute tours start at $25 to $35, but that doesn't give you much time to shoot. We used Adventurous Antelope Canyon Photo Tours and paid $106 each for a 31/2-hour tour. Guide Raymond Chee took us through Upper Antelope Canyon and a narrower area, accessible by ladders, known as Rattlesnake Canyon. If you're claustrophobic, don't attempt these tours. If you like semi-abstract nature photography, bring a sturdy tripod and expect to make long exposures.

For more info on guides and the park, go to https://www.lat.ms/1fcuhpq.

Before you head to Page, check the status of U.S. 89. Since a landslide on Feb. 20, a 23-mile stretch of highway has been closed between Page and Bitter Springs (to the south). As of the Travel section's deadline, Arizona officials had no timetable for reopening the road. Page remains accessible from the north by U.S. 89 (via Kanab) and from the south via U.S. 89T (during daylight hours) and Arizona State Route 98. More info: https://www.lat.ms/18lyuzx.

Between explorations, eat at Bonkers (810 N. Navajo Drive, Page; [928] 645-2706, https://www.bonkerspageaz.com). Yes, the name suggests a den of hard-partying college kids, but we had a nice Italian dinner amid handsome murals of sandstone arches and blue waters. Overnight, consider the Days Inn & Suites (961 N. Highway 89, Page; [928] 645-2800, https://www.daysinn.net). Rooms for two $80-$230, depending on season.

Arizona: Pistol of a picture at Monument Valley's John Ford's Point

This family business features a horse named Pistol, a camera and the epic vistas of Monument Valley from John Ford's Point.

Navajo Adrian Jackson with his trusty horse, Pistol, awaits the next group of tourists eager to snap pictures at John Ford's Point. ( Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times ) More photos

Five days a week, a young Navajo named Adrian Jackson pulls on a red shirt and cowboy hat and drives up a dirt road to John Ford's Point in Monument Valley. Then he spends the day sitting atop a horse named Pistol, trying to look epic, meeting travelers from around the world and helping them take pictures of one another sitting atop Pistol.

A photo by the jewelry tables? $2. Out on the point with the big vista? $5.

This is the family business.

John Cly did the job in the early 20th century. (You can see his red shirt, silver hair and furrowed brow, as photographed long ago by Josef Muench, in the popular tourist booklet "Monument Valley: The Story Behind the Scenery.")

Navajo Adrian Jackson sits atop Pistol at John Ford's Point. Jackson charges $5 for tourists to sit on his horse and to take pictures with a backdrop that legendary movie director John Ford used in several of his epic westerns. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times) More photos

After Cly came Adrian's grandfather, Frank Jackson, who did the job (again in red shirt) for about 40 years before his death in 2009. That's when Albert Jackson, Adrian's father, inherited the business and invited his son to handle the horse much of the time.

Adrian Jackson, 24, didn't always have this in mind. He went to college for a while in Phoenix to study electrical engineering. But he's back, applying his considerable charm when a Goulding's tour van rolls up and tourists climb out, savoring the landscape when it's quiet.

"It's pretty cool," he says, "when the fog comes in and starts covering the rocks."

Often while Jackson works with the horse, his girlfriend, Myra Watchman, is nearby selling jewelry or tending to their 2-year-old daughter, Amaya.

As for Pistol, 29 years old, succession plans are in place. Jackson estimates that Pistol is the fifth horse to do the job, which requires supreme equine calm. (Much of the time, the horse stands on a narrow outcropping above a 50-foot drop, with an unskilled tourist on its back.)

"After Pistol is gone, we have three horses who are going to alternate. So they won't wear out so fast," Jackson said. "They're a lot of fun to train."

christopher.reynolds@latimes.com

More Postcards From the West

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.