Advocates worry Black and Hispanic people are falling behind in census

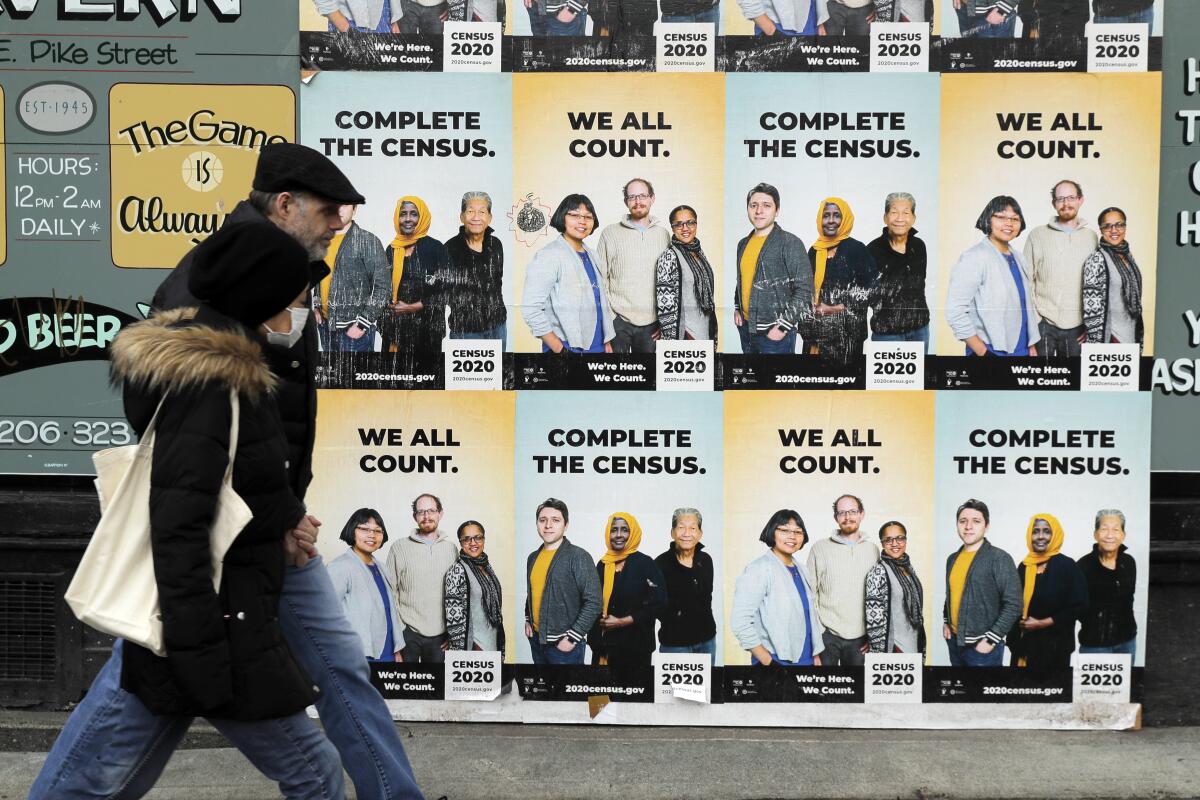

ORLANDO, Fla. — Halfway through the extended effort to count every U.S. resident, civil rights leaders worry that minority communities are falling behind in responding to the 2020 census.

With outreach efforts to motivate minority responses upended by a global pandemic, both the National Urban League and the NALEO Educational Fund are sounding the alarm that communities with concentrations of Black and Hispanic people have been trailing the rest of the nation in answering the census questionnaire.

The once-each-decade count helps determine where $1.5 trillion in federal funding goes and how many congressional seats each state gets.

“Going into 2020, we knew the census was going to be extremely challenging. We knew the Census Bureau didn’t have sufficient preparations to do all of its tests to make sure it would work out the way it should be ... and then COVID-19 hit,” said Arturo Vargas, chief executive of NALEO Educational Fund, said this week during a virtual town hall with NBCUniversal Telemundo.

The pandemic is disproportionately affecting the Latino population, he said, so “we have to figure out how we break through the real noise affecting their daily lives to do something as ordinary as going through the mail and filling out their forms.”

People can respond either online, by phone or through the mail, but many U.S. residents haven’t taken the initiative.

The nation’s self-response rate was 61.5% this week. Arizona, Florida, New Mexico, New York and Texas — states with large concentrations of Hispanic people — were lagging. California, which invested $187 million in outreach efforts, was doing slightly better, with 62.6% of its households responding, he said.

A more detailed analysis of response rates in late May and early June conducted by the Center for Urban Research at the City University of New York’s Graduate Center showed that neighborhoods with concentrations of Black residents had a self-response rate of 51%, compared with 53.8% for Hispanic-concentrated neighborhoods and 65.5% for white-dominant neighborhoods.

Voluntary response rates to the 2020 census reveal social inequality — and spotlight how crucial an accurate count is to Los Angeles and California.

Advocates at the National Urban League are particularly worried that the count will miss Black immigrants, Black people in rural communities, formerly incarcerated men and women, and children younger than 4.

The Census Bureau already plans to send out as many as 500,000 workers this summer and fall to the homes of people who haven’t responded, but the league’s president and CEO, Marc Morial, says it must do more — hiring still more door-knockers, targeting more advertising to minority communities and mailing out another round of paper questionnaires.

“They need to use their bully pulpit,” Morial said. “It’s been quiet.”

The Census Bureau had allotted $500 million for its outreach campaign. An additional $160 million was added after the start of the pandemic for advertising and engaging with community partners.

With the coronavirus spreading, the Census Bureau suspended field operations in mid-March for a month and a half, including efforts to drop off census forms at households in rural areas with no traditional addresses.

The census counts inmates as residents of the rural areas where they’re imprisoned. Critics say that practice siphons power from the urban areas which the mostly nonwhite inmates consider home.

The Census Bureau on Thursday said it had finished dropping off the forms to almost all of the 6.8 million mostly rural households. Because of the pandemic, the Census Bureau pushed back the deadline for finishing the 2020 census from the end of July to the end of October, and asked Congress for a delay in handing over apportionment and redistricting numbers.

Getting a higher self-response rate is important because it saves money on door-knocking and makes for a more accurate count. The 2010 census undercounted Black people by 2.1% and Hispanic people by 1.5%, according to the bureau.

“We are risking another decreased count in 2020 census,” Rep. Grace Meng (D-N.Y.) said Thursday during a conference call. Her Queens district is one of the most diverse in the nation.

“Any mistake or inaccurate count we make becomes a 10-year mistake and affects our neighborhoods and communities for a very long time,” she said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.