Hong Kong’s pro-democracy lawmakers resign en masse as Beijing’s grip tightens

- Share via

HONG KONG — Hong Kong’s autonomy from Beijing suffered another major blow Wednesday after pro-democracy lawmakers said they would resign en masse to protest the disqualification of four fellow pro-democracy legislators by the territory’s government.

The withdrawal of the 15 elected officials would essentially erase dissent in the legislature, which would be almost completely stacked with pro-Beijing lawmakers in a city where political opposition has been significantly curtailed by a new national security law imposed by the mainland Chinese government. That draconian law was enacted in June to quash months of unrest.

The lawmakers’ resignations, which they expect to submit Thursday, are in response to the ouster of four colleagues — Alvin Yeung, Dennis Kwok, Kwok Ka-ki and Kenneth Leung — under new powers granted by Beijing to disqualify legislators accused of supporting Hong Kong independence, refusing to acknowledge Chinese sovereignty or promoting foreign interference in the city’s affairs.

Pro-democracy legislators, speaking at a news conference Wednesday, declared Hong Kong’s fragile, separate constitutional system dead with Beijing’s latest move.

“Today is the end of ‘one country, two systems,’” Wu Chi-wai, convener of the pro-democracy camp, said of the special framework that was supposed to guarantee the territory a high degree of autonomy from Beijing for 50 years after the former British colony was turned over to China in 1997.

“Although we are facing a lot of difficulties in the coming future for the fight of democracy,” Wu said, “we will never, never give up.”

Wu added that the pro-democracy legislators would hand in their resignation letters Thursday. During the news conference, the lawmakers chanted, “Go, Hong Kong, together we stand,” while holding hands.

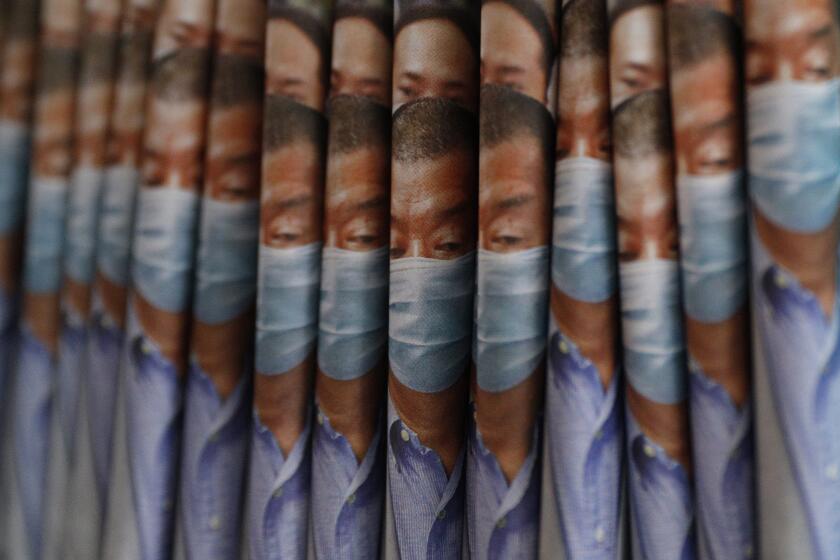

The raid this week of Apple Daily’s newsroom and leadership changes at broadcaster iCable highlight the shrinking space for independent journalism as Beijing exerts more control over a once freewheeling Hong Kong.

Hong Kong’s Beijing-approved leader, Carrie Lam, said in a news conference Wednesday that lawmakers must act properly and that the territory needed a legislature composed of patriots.

“We cannot allow members of the Legislative Council who have been judged in accordance with the law to be unable to fulfill the requirements and prerequisites for serving ... to continue to operate in the Legislative Council,” Lam said.

In Beijing, Foreign Ministry spokesman Wang Wenbin said that the move to disqualify the four lawmakers was necessary to maintain rule of law and constitutional order in Hong Kong.

“We firmly support the [Hong Kong] government in performing its duties in accordance with the Standing Committee’s decision,” Wang said, referring to China’s National People’s Congress Standing Committee, which approved a resolution this week granting the power to remove lawmakers.

Less than two weeks under a new national security law enacted by Beijing, Hong Kong residents already feel a curtain of control falling over the city’s realms of speech and thought.

Freedoms once common in the territory of 7 million have quickly eroded in response to months-long protests that gripped Hong Kong starting in March of last year and that have since gone silent because of the COVID-19 pandemic and new national security law.

Education officials have purged teachers sympathetic to the democracy movement and punished students who supported the demonstrations. A journalist who investigated police misconduct has been arrested, as have many pro-democracy activists.

Legal experts said the removal of the four lawmakers now calls into question the future of Hong Kong’s independent judiciary.

“The change means that even current lawmakers can be disqualified from office by a decision of an election official rather than by a court,” said Stuart Hargreaves, a law professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. “It serves to further neuter what was already by constitutional design a weak Legislative Council. It’s an open question as to whether similar moves to bring the judicial branch to heel will be made. It is essentially the only meaningful check on the government’s power.”

China’s ‘purification’ of classrooms: A new law erases history, silences teachers and rewrites books

China’s crackdown on Hong Kong is purging teachers, rewriting textbooks and increasing pressure on schools over what to put in the minds of students. A new national security law has endangered freedom of thought and expression.

Hong Kong’s legislature was established after the 1997 handover and is known less for groundbreaking laws than its members’ theatrical forms of dissent. Through dramatic gestures such as ripping up the constitution and even tossing a drinking glass, the opposition members have tried to annoy the city’s executive branch as the latter became more compliant with Beijing’s commands.

The four disqualified lawmakers had become targets of Beijing. Some of them had actively lobbied against the mainland government, even traveling to the United States to seek help in checking Beijing’s power.

Last year, during the height of demonstrations that were often broken up by tear gas and rubber bullets, several pro-democracy lawmakers tried to negotiate between protesters and police, expressing support for the youth-dominated movement.

Some legislators said Wednesday that they had faced pressure for years in a chamber where they never caucused with pro-Beijing forces. With the four democracy backers ejected, the remaining bloc members could not maintain enough support to block impeachment proceedings against their colleagues.

“When they are in control of the majority, everyone is at their mercy,” said Yeung, one of the disqualified legislators.

Breaking News

Get breaking news, investigations, analysis and more signature journalism from the Los Angeles Times in your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

In July, the local government used emergency powers to postpone September’s legislative elections by one year, citing a resurgence of coronavirus cases in the city despite one of the lowest rates of infection in the world.

Government critics and many voters viewed the decision as a deliberate move to squelch a wave of support for the opposition, which was expected to gain seats amid the fury over the national security law.

Weeks later, the government banned a dozen pro-democracy candidates from running in the next election, including Yeung and Dennis Kwok. They were accused by election officials of objecting to the new national security law, along with “soliciting foreign powers in relation to Hong Kong affairs” and “expressing an intention to abuse the power” of the Legislative Council.

The two met with U.S. lawmakers in the summer of 2019, hoping that intervention from Congress would compel Beijing to back off. A year later, President Trump signed a human rights bill and sanctioned Hong Kong officials deemed to have suppressed the democracy movement.

After the Hong Kong elections were canceled, several of their colleagues quit, saying it was wrong to give legitimacy to Beijing’s actions. Yeung said it was important to avert, or at least slow down, pro-Beijing initiatives. Most notably, he said, some pro-Beijing members wanted to set up an investigative committee to look into the democracy movement and the money that fueled last year’s protests.

“If that was allowed, that would have become a witch hunt,” Yeung said.

Beijing is using the coronavirus crisis to crush Hong Kong’s demands for more freedom, thinking the world is too busy to care.

If the members had decided to stay, the national security law would have created potential security risks for those who defied Beijing’s orders or opposed legislation.

In recent years, pro-democracy members have tried to stop laws increasing China’s control, including imposition of the Chinese national anthem on Hong Kong and an order that part of the city’s new rail terminus be under the jurisdiction of mainland security law.

Wednesday’s move to disqualify opposition legislators removes one of the few remaining obstacles in Beijing’s way, pro-democracy lawmaker Claudia Mo said.

“This is an actual act by Beijing ... to sound the death knell of Hong Kong’s democracy fight, because they would think that from now on anyone they found to be politically incorrect or unpatriotic or ... simply not likable to look at, they could just oust you using any means,” she said.

Sataline is a special correspondent. Times staff writer David Pierson in Singapore and the Associated Press contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.