Report blames poor welds for deadly Mexico City subway collapse

MEXICO CITY — A preliminary report by experts on the deadly collapse of a Mexico City elevated subway line has placed much of the blame on poor welds in studs that joined steel support beams to a concrete layer supporting the track bed.

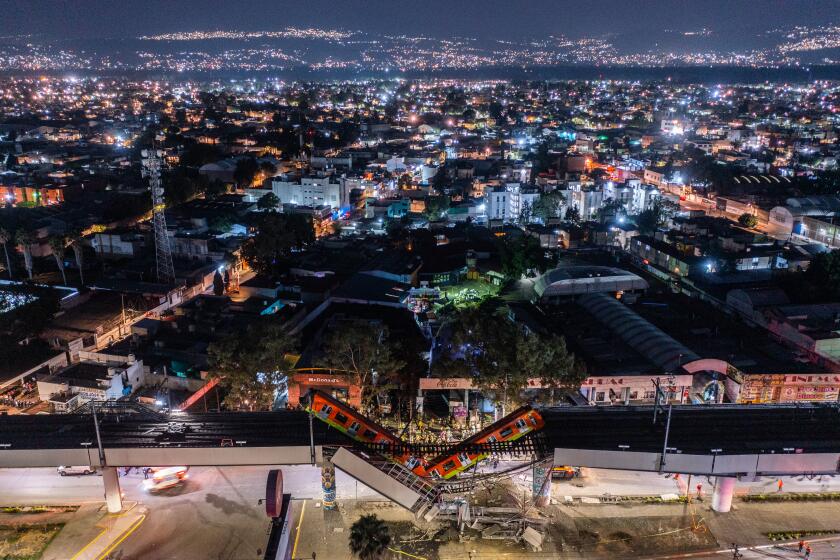

The city government hired Norwegian certification firm DNV to study the possible causes of the May 3 accident, in which a span of the elevated line buckled, causing two subway cars to plunge to the ground. The collapse killed 26 people.

The report, released Wednesday, also said that there were apparently not enough studs and that the concrete poured over them may have been defective. The welds between stretches of steel beams appeared to have been badly done.

“The studs showed deficiencies in the welding process,” the report said.

The existence of construction defects when the line was built between 2010 and 2012 could be a major blow to the political career of Mexico’s top diplomat, who was mayor at the time, and to Mexico’s richest man, whose company built part of the subway line.

The report centered on photos and physical inspection that showed that metal studs welded to the top of steel support beams had broken or sheared off cleanly, suggesting that the welds were defective.

A decision to change cars to be closer to a station exit may have saved Erik Bravo when a Mexico City subway line collapsed, killing 25 people.

The beams could not carry the weight of the track bed on their own. The studs projecting upward from the beams were covered with a poured concrete slab meant to help carry the weight.

But the studs were found to be still carrying ceramic rings that covered the welds. Used as a safety and control method to contain the molten steel, the rings were supposed to have been knocked off after welding so inspectors could see the welds themselves. The fact they were left in place may suggest that the welds were not properly inspected.

That would fit in with reports that the project was rushed to completion so that the Line 12 could be inaugurated by current Foreign Secretary Marcelo Ebrard before he left office as mayor in 2012.

The section was built by a company owned by telecom and construction magnate Carlos Slim, currently Mexico’s richest man and once the world’s wealthiest. Slim is an engineer by training, and his firms are currently involved in building some parts of the controversial Maya Train project, which will circle the Yucatan Peninsula.

At least 23 people died in an overpass collapse on the Mexico City Metro, which is among the busiest in the world.

Any suggestions that his firm did shoddy work on the subway would be a serious blow to his reputation as a sort of elder statesman of the Mexican business community.

The $1.3-billion Line 12, the newest section of a vast subway system that opened in 1969, was ill-fated from the start. The so-called Gold Line cost 50% more than projected, suffered repeated construction delays and was hit with allegations of design flaws, corruption and conflicts of interest.

A top executive of one of the companies that built it was the brother of the man who oversaw the project for the government.

The scandal over the forced closure of the costly new line in 2014 — just 17 months after it was inaugurated — essentially forced Ebrard into political exile. He was rescued by his patron, new President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who had helped make him mayor in 2006 and resuscitated his political career by naming him Foreign secretary in 2018.

Recriminations and allegations of shoddy maintenance and corruption emerge in the wake of train crash that killed 26.

Despite the subway scandal, Ebrard was put in charge of Mexico’s efforts to obtain COVID-19 vaccines and was once considered a top contender to succeed López Obrador in 2024.

Ebrard has said he’ll cooperate with investigations into last month’s accident. In a statement Wednesday, he said the subway line was planned, designed and built with help from “the best of Mexican engineers.”

“Identifying the causes of the accident is a necessary step in achieving justice for the victims of the tragedy,” Ebrard wrote.

But previous reports by engineering firms revealed Ebrard’s city government had made a series of startlingly wrong choices when the subway line was designed and built.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Experts said unusually sharp curves in the route exacerbated problems with the wheels-on-steel track design, which more resembles New York’s subway rather than the European-style rubber tires used on the rest of the system.

Line 12 chattered, bumped and shrieked. The rails began to take on a wavy pattern. Drivers had to slow trains to a 3-mph crawl on some stretches.

In 2014, the line had to be shut down for months for the tracks to be replaced or ground into shape.

Ballast was added between the train’s tracks during those repairs, and some say the extra weight and possible poor maintenance could have been factors in the collapse.

An official 2017 survey of damage from a deadly magnitude 7.1 earthquake showed indications of construction defects. Authorities decided on quick patches, welding props under the bowed beams and reopening service.

Ebrard has argued that subsequent investigations showed the line was judged to comply with standards when it was built. He wrote that “the supervision and maintenance that was up to the administration that succeeded mine remains in large part an unknown.”

Following earlier investigations into the design and corruption, more than 38 government employees were hit with fines or other punishments for improperly contracting out work on the train, as well as some criminal charges.

Since the May accident, much of the line has been closed. The elevated portion of the tracks rise about 16 feet above a median strip and roadway in the poor southern borough of Tlahuac.

Mexico City’s subway, which serves 4.6 million riders every day, has never had the one thing it needs most: money. With ticket prices stuck at 25 cents per ride, one of the lowest rates in the world, the system has never come close to paying its own costs and depends on massive government subsidies.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.