Coronavirus is turning an overloaded immigration system into a ‘tinderbox’

Last week, immigration Judge Ashley Tabaddor cordoned off the first row of seats in her courtroom at Los Angeles Immigration Court. Interpreters brought their own headsets. Clerks carried disinfectant wipes.

And some judges limited the number of people inside courtrooms, which normally are packed shoulder-to-shoulder.

Workers said they are doing their best to limit their and the public’s exposure to the coronavirus and COVID-19 in the face of what they describe as insufficient protective measures taken by federal officials.

“There’s only so much judges can do in their own spheres. They don’t have any control over waiting areas or the rest of the court,” said Tabaddor, president of the National Assn. of Immigration Judges.

She described the federal response as “just sticking their heads in the sand, hoping it will all go away.”

Across the nation, immigration judges, attorneys and immigrant-rights advocates, as well as some federal immigration workers, are calling on the federal government to take aggressive steps to slow the spread of the virus and its effect on an already overloaded and backlogged immigration system.

On Wednesday, two dozen Democratic senators led by Sen. Kamala Harris of California sent a letter to the acting chiefs of Homeland Security, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and U.S. Customs and Border Protection asking about their coronavirus response.

“Given the spread of the virus in the U.S. — and the particular vulnerability of individuals in immigration detention and staff — it is critical that DHS, ICE, and CBP have plans to help prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus at DHS facilities and to protect detained persons, facility staff, and the general public,” the senators wrote.

The immigration system is being severely tested in multiple ways. Immigration judges, attorneys and prosecutors also have called on all immigration courts to shut down. Immigrant-rights activists and public health academics insist that detention centers should release immigrants and suspend most immigration arrests and deportations.

But the looming crisis goes far beyond issues of overcrowding and exposure. In the field, a lack of clear guidelines across the immigration system is exacerbating delays in processing of immigrants. The virus also is likely to disrupt the flow of foreign workers and could hamper the government’s ability to staff agencies that process immigrants and asylum seekers.

Among the most pressing concerns is the inability to implement social distancing in institutional settings, specifically immigration courts and detention centers.

“It’s a tinderbox,” said Wendy Parmet, a professor of law and public health at Northeastern University. “Whatever you think about criminal justice reform in the long term, detention and congregation of people in institutional settings is dangerous right now. It’s dangerous for people detained. It’s dangerous for the staff. It’s dangerous for the community who interact with the staff.”

For days now, government officials have urged the public to distance themselves physically from others. But that’s hard to accomplish in small immigration courtrooms often packed with dozens of people and immigration detention centers where people are held in tight quarters and share bathrooms.

U.S. immigration courts are already grappling with a backlog of more than 1 million cases. For years, immigration judges have processed immigrants in large groups in an attempt to speed up the system. But the numbers have tripled under the Trump administration, which has doubled down on immigration enforcement. In that time, apprehensions have dropped but immigration judges say they are overloaded with cases; in recent months, several judges have resigned in protest.

The crisis has made for uncommon alliances.

Last weekend, Immigration and Customs Enforcement Professionals Union joined the National Assn. of Immigration Judges and American Immigration Lawyers Assn. in calling for the federal government to close all of its 68 immigration courts for two to four weeks.

In an open letter, the judges and lawyers groups said the Trump administration has told them that the spread of COVID-19 was insufficient and not based on transparent science enough to warrant wide closure.

“The DOJ is failing to meet its obligations to ensure a safe and healthy enforcement within our Immigration Courts,” the statement said.

Late Tuesday, the Executive Office for Immigration Review, which manages the immigration court system, announced it would close the downtown Los Angeles Immigration Court and postpone non-detainee hearings at immigration courthouses across the country. The move effectively closed 10 courthouses, including Sacramento, New York City and Houston, until April 10.

But several courthouses remained open for cases with detained immigrants, among them San Francisco San Diego and Tacoma, Wash. The Seattle Immigration Court was the first to close last week because of a high number of cases in the area and after there was a reported second-hand exposure.

Last week in New York City, immigration attorney Bryan Johnson wore a gas mask on a train from his home in Long Island to immigration court in New York City because he had to appear for trial.

Days later, Johnson and other immigration attorneys urged others to stay away.

“We will not appear for immigration court hearing during #coronavirus pandemic, even if an adjournment request is denied,” Johnson put on his Facebook page. “We will not allow EOIR’s recklessness in keeping court open to cause serious harm to us, our clients, our staff, or our clients.”

On Tuesday, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services announced it would temporarily close all immigration offices until April 1 because of the virus. The move postpones asylum and citizenship interviews, as well as naturalization ceremonies. The agency’s employees were encouraged to work from home, and others, including asylum officers, were recalled from detention facilities and postings across the country.

“At a time when the federal government should be leading by example ... DHS and USCIS have been putting staff and all who have business with our agency at risk,” one USCIS employee told The Times on condition of anonymity to protect against professional retaliation. The employee has been sick but unable to get tested for COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus. “It’s shameful.”

U.S. immigration authorities could soon begin closing the southern border to certain migrants, removing those who enter the U.S. between official ports of entry and turning them back to Mexico to limit the pandemic, officials told The Times. The administration has yet to formally announce the proposal,but it is hammering out final details.

On Tuesday, administration officials began laying the groundwork for the shift. Under the new policy, Border Patrol agents who apprehend Mexican adults attempting to cross the border between ports of entry will return them to Mexico at a nearby port of entry instead of detaining them, according to Brandon Judd, president of the union that represents 15,000 agents, the National Border Patrol Council.

As of Tuesday, no U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents or migrants in custody had tested positive for the coronavirus, Judd said.

Nathan Peeters, a Border Patrol spokesman, would not say how many agents and detained migrants had been screened for COVID-19 as of Tuesday. Those with symptoms or whose travel history was flagged were referred to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or local health officials for added screening, he said, and the agency issued staff masks — including N95 respirators — gloves, goggles and disposable outer garments to prevent the spread of the virus and COVID-19.

During a briefing Thursday, Acting Border Patrol Commissioner Mark Morgan said that the agency was “monitoring and aggressively pursuing all opportunities to contain and mitigate” coronavirus.

“The health risk threat along the southwest border is very real,” Morgan said.

Morgan said that migrants caught illegally crossing the southern border were subject to the same coronavirus screening as international travelers arriving at U.S. airports.

Another area where the virus could affect immigration is by stemming the flow of agricultural guest workers into the country. This week, the U.S. Embassy and consulates in Mexico suspended visa services, which farm labor contractors say could deal a blow to the strawberry and apple industries.

The deportation system is yet another area of uncertainty. On Tuesday, Guatemalan officials suspended all deportation flights originating from the U.S. until new health screening protocols are developed. The move will have a significant effect on the Trump administration’s efforts to ramp up a controversial agreement under which the U.S. sends migrants who are seeking asylum in the U.S. to Guatemala.

Los Angeles ICE Director Dave Marin said Mexico likely would follow suit.

“I think with removal flights, they can be fairly confident that they have been medically cleared,” he said, noting that they’re taking temperatures. “Whereas, anyone flying commercial, they can’t control that.”

He said stopping all deportation flights could have a huge impact on the agency.

“We’d get backed up,” he said.

The rapid spread of the virus also is posing challenges for immigrants being held in detention and the agencies responsible for them. On Friday, ICE announced the suspension of social visitations at its detention centers.

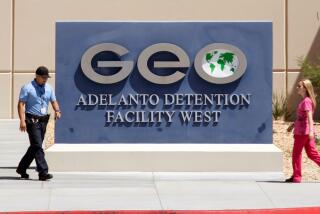

The privately run federal immigration detention center in Adelanto, 85 miles northeast of Los Angeles, which is capable of holding 1,900 immigrants, would likely reach capacity in a few weeks, Marin said.

On Monday, the ACLU and other groups launched a lawsuit against ICE, calling for the release of immigrants in detention who are particularly vulnerable to COVID-19. Advocates said that detainees are particularly vulnerable to outbreaks of contagious illnesses because they live in close quarters and are often in poor health. They noted that medical care in ICE facilities has been documented to be inadequate, such as the 14,000 health and safety deficiencies identified by the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Inspector General.

In a letter to ICE field office leaders in Los Angeles and the warden of the Adelanto ICE Processing Center in San Bernardino County, lawyers with Immigrant Defenders noted that COVID-19 is unlike any infectious disease that Adelanto has experienced.

“Its transmission rate will be significantly higher than that of mumps, measles, or chickenpox, because no so-called ‘herd immunity’ exists against the virus, i.e., there is no population with immunity,” lawyers wrote. “Simply put, persons detained at [Adelanto detention facility] are sitting ducks for a fatal COVID-19 infection.”

The lawyers said ICE should use its discretion to release detainees under humanitarian parole and use alternatives to detention, such as GPS ankle monitors and home visits.

Besides Adelanto, ICE houses detainees in four other California facilities: the Yuba County Jail in Marysville, Mesa Verde ICE Processing Facility in Bakersfield, Otay Mesa Detention Center in San Diego and Imperial Regional Detention Facility in Calexico.

Lizbeth Alben of the Inland Coalition for Immigrant Justice said officials at Adelanto started sanitizing the facility on Monday in response to coronavirus concerns, which means detainees are kept for long periods in their cells without recreation time or phone access.

One detainee there, Jose Topete, said Monday that detention staff placed CDC posters about COVID-19 around the facility but only in English. He said ICE agents have entered the facility wearing masks and gloves, leaving detainees panicked.

“We’re scared,” he said. “What is going to happen with us?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.