Column: Woke California pays homage this week to another American hero with a complex legacy

Let me tell you about an American hero whom the San Francisco Unified School District Board of Education might find, um, troublesome.

He opposed undocumented immigrants to the point of urging his followers to report them to la migra. He accepted an all-expenses-paid trip from a repressive government and gladly received an award from its ruthless dictator despite pleas from activists not to do so.

He paid his staff next to nothing. Undercut his organization with an authoritarian style that pushed away dozens of talented staffers and contrasted sharply with the people-power principles he publicly espoused. And left behind a conflicted legacy nowhere near pure enough for today’s woke warriors.

A long-dead white man? A titan of the business world? Perhaps a local politician?

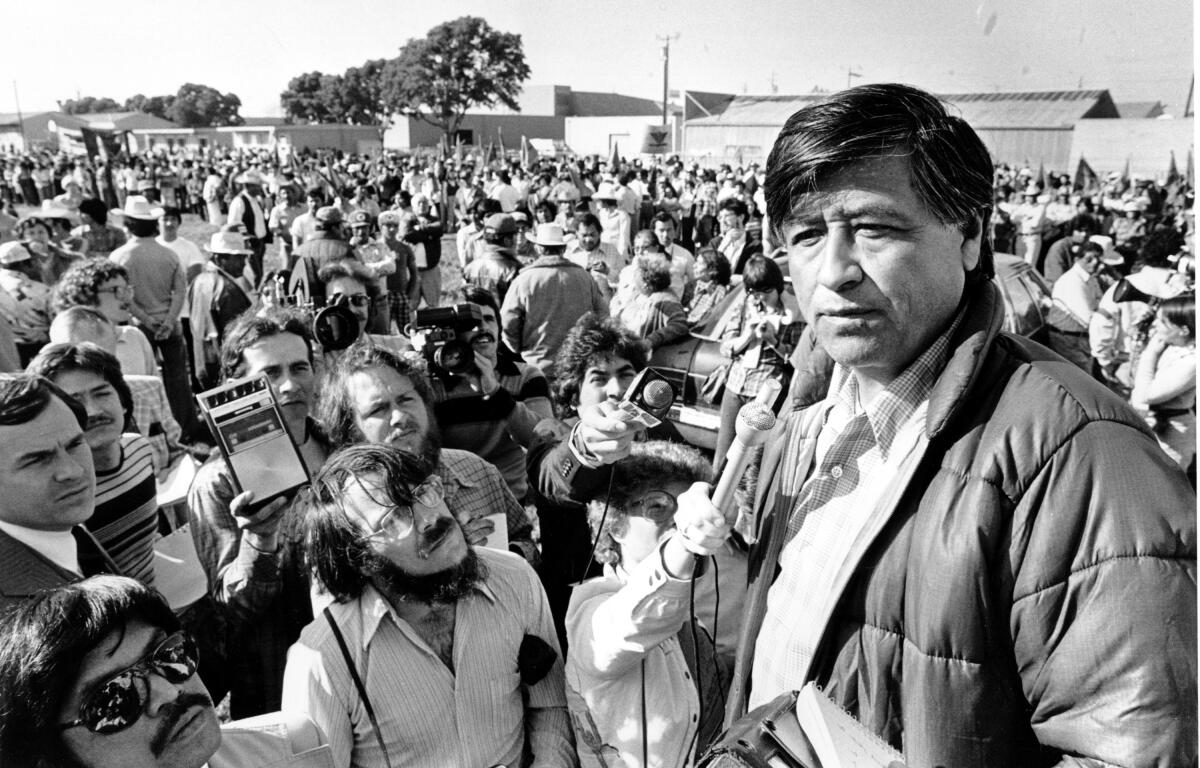

Try Cesar Chavez. The United Farm Workers founder is the first person I always think about whenever there’s talk about canceling people from the past. He’s on my mind again, and not just because this Wednesday is his birthday, an official California holiday.

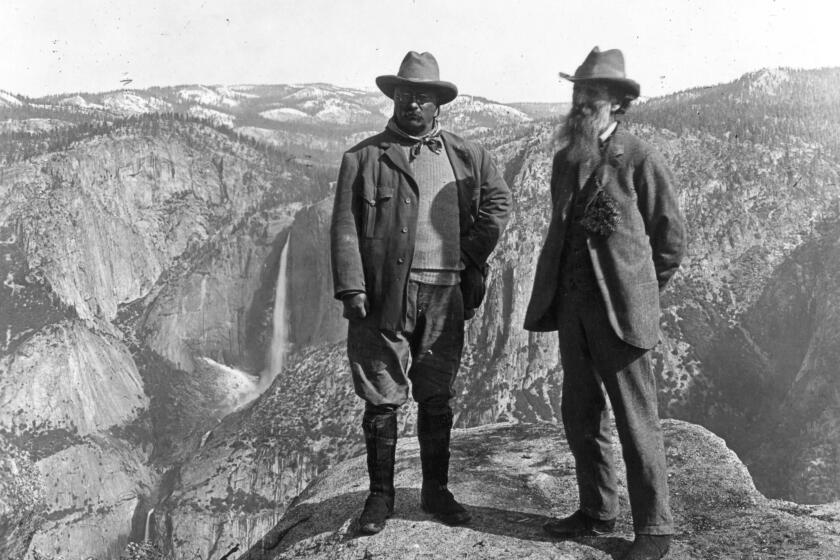

On Jan. 27, the San Francisco school board voted to rename 44 schools that it felt honored people who didn’t deserve the homage. Some of the condemned make sense — Father Junipero Serra, for instance, or Commodore John Sloat, the Navy officer who conquered California in the name of Manifest Destiny. Others are worthy of debate. Should we really champion Thomas Jefferson, the writer of the Declaration of Independence who also fathered multiple children with his slave, Sally Hemings? Or John Muir, the beloved naturalist who didn’t think much of Black and Indigenous people?

The Sierra Club acknowledges the racist history of its co-founder, the famed environmentalist John Muir.

The board’s move was rightfully met with disbelief and derision. In a year when parents are clamoring for schools to reopen, this is what board members spent their time on? And are kids really harmed if they attend a school named after Robert Louis Stevenson or Paul Revere?

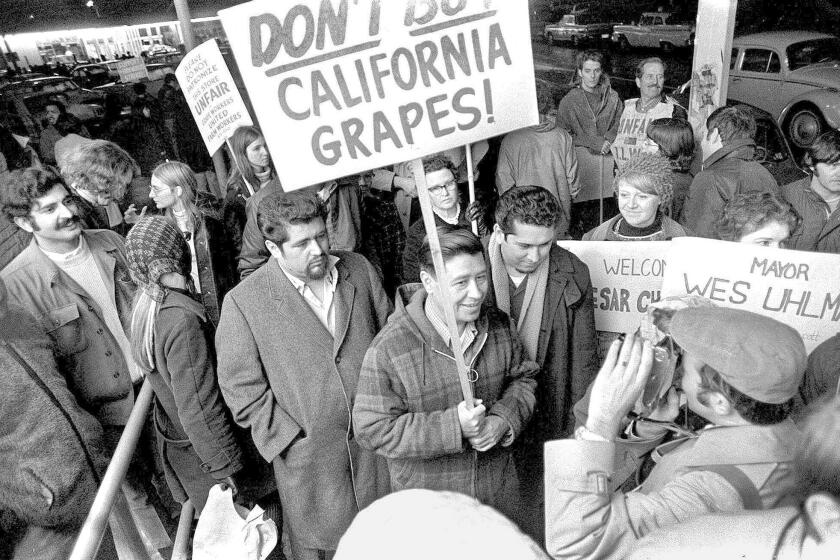

Which brings us back to Chavez, the revered labor leader whose bust President Biden recently put on prominent display behind his desk in the Oval Office. On Wednesday, First Lady Jill Biden will travel to Delano, Calif., to celebrate the state holiday with the Cesar Chavez and United Farm Workers foundations, her office announced over the weekend.

Joe Biden is already making a memorable mark in the White House, honoring beloved Mexican American figure Cesar Chavez in the Oval Office.

He remains by far the most famous Latino activist in this nation’s history, a modern-day secular saint of whom former President Obama said when he dedicated the Cesar E. Chavez National Monument in Kern County in 2012 “refused to scale back his dreams. He just kept fasting and marching and speaking out, confident that his day would come.”

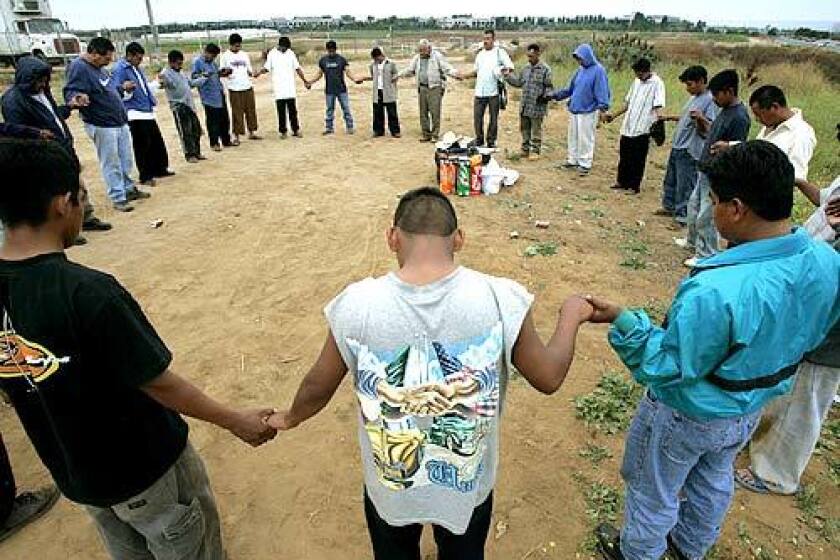

Chavez’s main cause — bringing dignity to farmworkers — remains so radical and righteous that to criticize his personal failures is still largely verboten.

That’s why there was never any call by the San Francisco school board to remove Chavez’s name from an elementary school in the Mission District. Or for the same fate to befall city schools named after Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, even though the former once advised a teenage boy in Ebony magazine that his homosexuality was a “problem,” while the latter called white people “devils” and spoke at a rally along with the head of the American Nazi Party.

History — life — is not an easy-peasy snap-judgment call. To paraphrase Oscar Wilde: Every saint had a past, and every sinner has a future. And Chavez is perhaps as great an example of this in California history. It’s a thought that took me my adult life to realize and appreciate — and accept.

I remember when I first heard about him: freshman year in high school, when my white teacher lectured that he was a grand warrior for Mexican Americans like me. I agreed — and then realized my teacher wasn’t talking about the legendary Mexican boxer Julio Cesar Chavez. When I asked my mom — who was picking strawberries in El Toro as a teenager when the UFW was winning national attention — if she knew who Chavez was, Mami didn’t have a clue.

But once I learned the basics about his life — his marches, boycotts and famous hunger strikes; his embrace of social justice and an ascetic lifestyle; his use of Mexican motifs like the stylized Aztec eagle that serves as the UFW’s symbol — Chavez entered my pantheon of heroes through my college years.

That changed in graduate school, when I read a 1992 memoir by Philip Vera Cruz. The Filipino immigrant was already a legendary labor organizer when he helped Chavez establish the UFW and stayed by his side until 1977, when he criticized Chavez for hanging out with the Philippines’ president, Ferdinand Marcos, and quit.

Vera Cruz’s memoir decried the organization he helped to found as turning “very ethnocentric. When [UFW Mexican members] called out ‘Viva la Raza’ or ‘Viva César Chávez,’ they didn’t realize that all these ‘Vivas’ did not include the Filipinos,” he wrote. “As a matter of fact, they didn’t include anyone but themselves.”

I didn’t even know until reading Vera Cruz’s book that Filipinos helped to start the original grape strike that led to the UFW.

I learned more about Chavez’s faults as I progressed through my journalism career. How he once lashed out at Dolores Huerta — who had urged him to use more sympathetic language for immigrants in the country illegally than “wetbacks” — by saying, “You [Chicano liberals] get these hang-ups.… They’re wets, you know. They’re wets, and let’s go after them.” How he organized group exercises for UFW higher-ups that consisted of people taking turns screaming and intimidating others over their perceived faults.

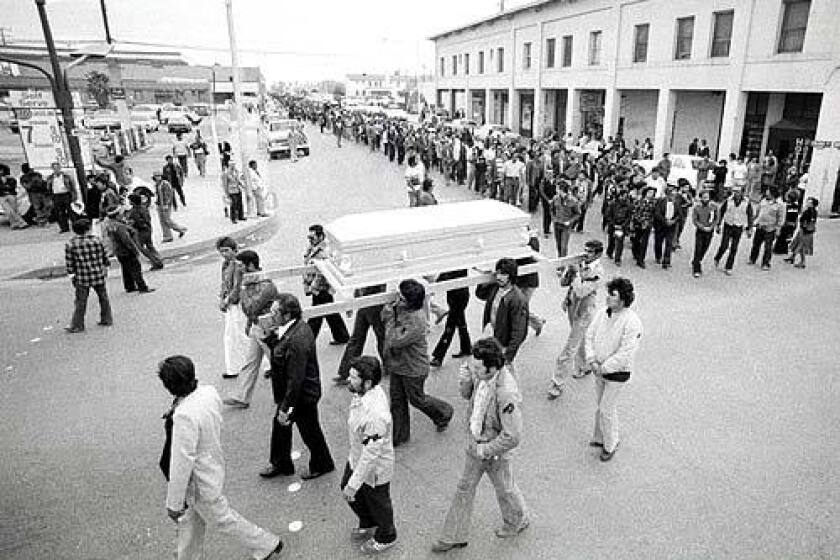

In the late 1970s Cesar Chavez grew intent on keeping control. He crushed dissent, turned against friends, purged staff and sought a new course.

My immature mind decided he could be a hero to me no more, and so he wasn’t.

As the years went on, I delighted in pointing out his bad deeds whenever possible. I took as inspiration the work of Miriam Pawel, a writer, who in the pages of this paper in the mid-2000s detailed a UFW that she painted as far removed from the union Chavez and others had established. She continued her work with a well-received 2014 biography on him that I just got around to reading this past pandemic year.

The movement built by Cesar Chavez has failed to expand on its early successes organizing rural laborers. As their plight is used to attract donations that benefit others, services for those in the fi

I’m friendly with Pawel, so I’d send progress reports as I went through her book. It confirmed in wrenching detail why I felt Chavez wasn’t worthy of adulation, I thought. She encouraged me to read it all the way to the end, where I’d find a “surprise.”

And there it is, on Page 475: Pawel asked a former Arizona UFW leader who had parted ways with Chavez long ago whether he still thought of him as a great man. “Palms up, he held his right hand above his head and lowered his left near the floor,” Pawel wrote. “On balance, he said, the good outweighed the bad. It was not even close.”

Boom.

When I asked Pawel recently if problematic people like Chavez should have their names stricken from schools and other monuments, her answer was quick: “Of course not. The fact that heroes have flaws don’t make them any less heroic. We’ve gone from hagiography to tearing people down.”

Miriam Pawel’s ‘The Crusades of Cesar Chavez’ gives the labor leader credit for his stunning accomplishments but does not shy from his failures, paranoia and dictatorial style.

During her book tour, Pawel feared that audience members might take issue with all the Chavez warts her book exposed. “But the responses was, ‘Yeah, we get it, we get he was human,’” she said. “They were not surprised to hear that he was more complicated than a two-dimensional postage stamp.”

And so on Cesar Chavez Day, let’s remember that the hero was a man. And that Man, invariably, is no saint.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.