Can a tsunami happen in Southern California? What should you do about it?

Walking back to parking lot three at Santa Monica State Beach after spending a sunny day lounging in the sand, perhaps you noticed one of the blue and white “Tsunami Hazard Zone” signs but didn’t think much of it.

In California more than 150 tsunamis have hit the coastline since 1880. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 42 of the 150 occurred in Los Angeles County.

Considering that California is hit by about one tsunami a year, it’s time to take more notice of those hazard zone and evacuation route signs.

If you’re asking yourself why you haven’t heard about all these tsunamis hitting California, it’s because a majority of those recorded were barely noticeable, and few have caused fatalities or significant damage, said Nick Graehl, engineering geologist for the California Geological Survey.

The last recorded tsunami here occurred July 29. It was generated by an 8.2 earthquake off the Alaska Peninsula but brought less than one foot of water to our shores. The most recent damaging tsunami occurred in 2011 when an earthquake and tsunami that devastated Japan traveled across the Pacific Ocean, causing $100 million of damage to California harbors and ports.

A Californian who lives or works near the coast or who’s planning a summer beach day should have a plan just in case a large tsunami comes our way.

How will I know a tsunami is coming?

The natural warning signs can include feeling a strong or long earthquake. Also, if you see a sudden rise or fall of the ocean or hear a loud roar from the ocean, it’s time to head inland.

The National Weather Service is a governmental agency that operates two tsunami warning centers, with a goal of monitoring for tsunamis and the earthquakes that may cause them, and sends tsunami alerts. To get official notifications of a tsunami warning, sign up for text message alerts from your local government, get a battery powered NOAA weather radio or listen for TV, radio, or automated telephone announcements.

Sign up for alerts from:

- The National Weather Service Tsunami Warning System

- The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Weather Radio

- NOAA Wireless Emergency Alerts Capable

Not all earthquakes will cause a tsunami. But if you feel or see any natural warning signs, Graehl stressed that you should immediately move to higher ground.

MyShake is the early-warning app recommended for Southern Californians. But there are others you can download. What are they and which ones might you want?

What do I do during a tsunami?

Evacuate the area by foot and get to higher ground. Don’t get in your car and try to drive away from the hazardous area — evacuating by car could create a traffic jam.

If you feel the earthquake: drop to the floor, take cover, and hold on until the shaking stops.

If you evacuated from a coastal area, stay away until officials permit you to return.

Do not go toward the coast to watch a tsunami. Tsunamis move faster than a person can run.

Do not attempt to surf a tsunami. Regular waves flow in a circle without flooding higher areas. Tsunami waves are unpredictable and flood the land like a wall of water.

When the Big One hits, will Californians be ready for a lack of modern communication connections? Extended periods without essential utilities such as water and gas? Damage to homes? The mental health effects that often follow disaster?

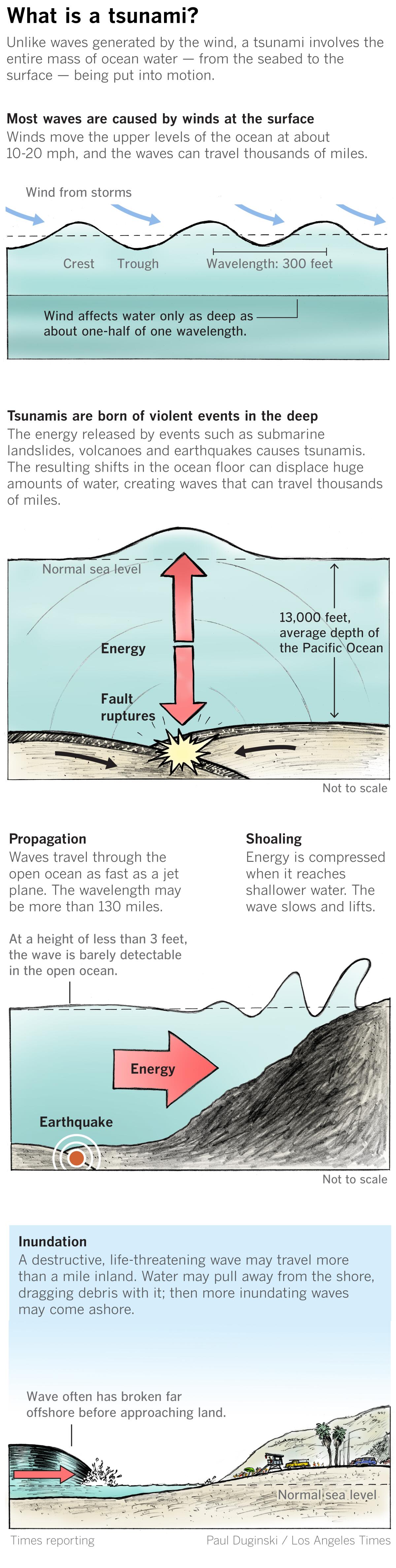

How tsunamis happen

Most tsunamis are caused by large earthquakes below the ocean floor, but they can also be caused by landslides, volcanic activity and certain types of weather. An asteroid or comet striking the earth could also do it.

In an earthquake-caused tsunami, underwater tectonic plates shift, causing the quake and displacing water. Waves are generated and move out in all directions across the ocean, some traveling as fast as 600 mph. As waves enter shallower water, they compress, their speed slows, and they build in height, pushing water ashore. What we experience on land wouldn’t be the common misperception of a massive wave that a surfer could ride all the way to the 405 Freeway. It’s more like a surge of water that rushes inland, threatening anyone and anything in its path. Tsunamis aren’t just a single wave, either — they can last for hours and cause devastation miles inland, as Japan experienced in 2011.

There are two types of tsunamis: a local-source tsunami and distant-source tsunami.

A distant-source tsunami is generated by an earthquake from a far-away source. It could take five to 13 hours to arrive here depending on where it originates. In that case, there would be time to issue a warning and for people to evacuate.

Distant-source tsunamis typically come from Japan, Chile or Alaska. Graehl said the worst-case scenario for Southern California is a tsunami generated from the eastern Aleutian Islands in Alaska. It would take five to six hours to arrive — providing some time for notification and evacuation. When it did arrive, though, it could produce more than one significantly large surge.

A local-source tsunami, or a near-field tsunami, can be generated by sudden movement of offshore faults or underwater landslides. Because this type of tsunami is generated from a nearby source, it could arrive in minutes.

Graehl said Northern California could experience a significant local tsunami event generated from a major earthquake on the Cascadia Subduction Zone fault — a 700-mile undersea boundary where tectonic plates are colliding — that stretches from Northern Vancouver Island to California’s Cape Mendocino. This type of event could cause at least six minutes of shaking, giving people 10 minutes before surges of water of up to 50 feet high hit Crescent City, which has the highest tsunami risk in the state.

In Southern California, Graehl said, a distant- or local-source tsunami could look like swirling currents in the bay or a wall of water, up to 10 to 25 feet.

People are much more important than kits. People will help each other when the power is out or they are thirsty. And people will help a community rebuild and keep Southern California a place we all want to live after a major quake.

How to prepare for a tsunami

- Get your local tsunami evacuation map. The California Department of Conservation released updated interactive hazard maps this year, a tool to help plan a safe evacuation route. The new map includes a function that allows users to look up addresses to see if that location is in a designated tsunami hazard zone (highlighted in yellow). Find your specific map at conservation.ca.gov/cgs/tsunami/maps.

- Practice your evacuation route.

- Put together or purchase an emergency “go bag” containing at least 72 hours of supplies.

- Boaters, contact your local harbor master or local officials to learn about your harbor’s tsunami safety protocols.

In Southern California in particular, the chances of a smaller tsunami occurring are higher than a large one.

“A smaller-sized tsunami might not flood a grain of sand that doesn’t normally get flooded in high tide, but it could cause strong and unusual currents in beaches, harbors, and bays,” Graehl said.

Don Drysdale, spokesperson for the California Geological Survey, said you shouldn’t be on high alert at all times, but it’s something to think about if you’re on a crowded beach on Labor Day.

He went on to say that he understands that people in California have a lot to consider when it comes to safety — wildfires or earthquakes, to name a few.

“So we’re not trying to add to people’s plate, but it is something that they need to be aware of and have in the back of their minds,” Drysdale said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.