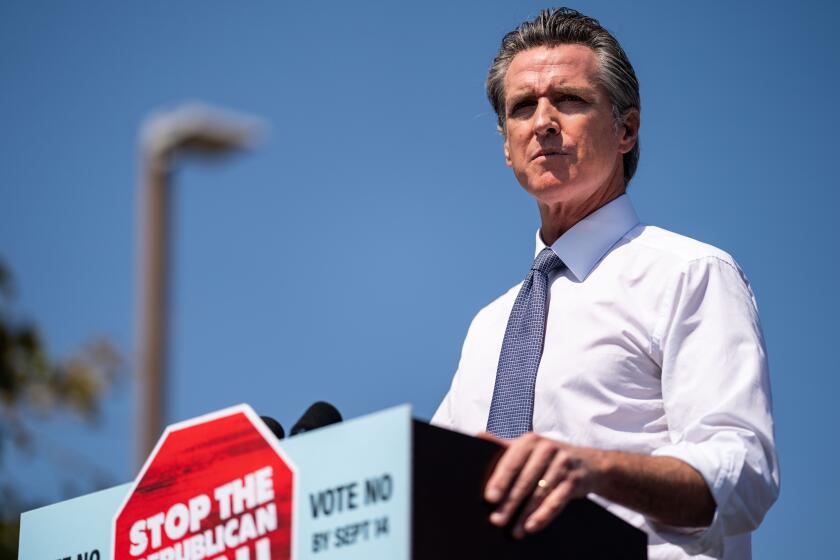

Newsom beat the recall. Will he take any lessons from it?

SACRAMENTO — Twenty-six days before his 54th birthday, California voters gave Gov. Gavin Newsom the early gift of a second chance.

Their refusal Tuesday to remove him from office brings to an end a dramatic and disagreeable chapter in the state’s political history, though the clashes sparked by the recall election will surely persist into next year and beyond.

But while Newsom can rightly boast that a sizable majority of voters want him to finish the term to which he was elected in 2018, the election returns offer no such mandate for his style of governing.

The governor’s anti-recall campaign rarely mentioned his accomplishments. Instead, it relied on the political equivalent of a screaming security alarm, warning that voters should take a good look at the Republicans whose special election, the Democrat’s campaign insisted, amounted to attempted theft.

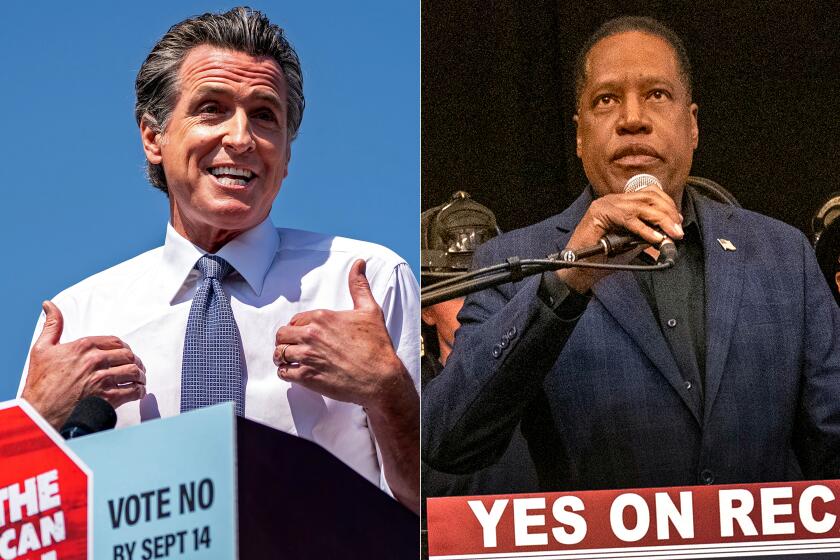

Newsom’s political team didn’t stop there. Its closing argument was that a dystopian future was on the horizon should any of the GOP hopefuls — most notably conservative talk radio host Larry Elder — take the oath of office and dismantle California’s efforts to fight the COVID-19 pandemic.

In some ways, the anti-recall campaign borrowed from the bruising fight Newsom waged against then-President Trump during their two years of overlap in office. As election day arrived, the governor argued that Elder was a California-grown Trump knockoff, an accusation endorsed on Monday by President Biden during a rally in Long Beach.

The election provided California voters an opportunity to judge Gov. Gavin Newsom’s ability to lead the state through the COVID-19 pandemic, a worldwide health crisis that has shattered families and livelihoods.

But the campaign is over. And what Newsom takes from what happened — what he does or doesn’t learn from it — will affect millions of Californians.

And though he prevailed, some will counsel him to show gratitude after surviving what was akin to a political near-death experience.

“I think after politicians score a major victory, they should show a little bit of humility,” said Garry South, a strategist who worked with Newsom on his brief dalliance with running for governor in 2009. “I’m not one who believes that Democrats need to reach out to the Trump voters, but there are well-meaning Californians who probably signed the recall petition.”

Neither Newsom nor his fellow Democrats may believe that means going so far as to offer an apology. But the idea of bridge-building after a highly polarized battle has some historical precedent.

In 2005, then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger made a full mea culpa after voters soundly rejected all four of the measures he placed on a special election ballot, proposals that read like a conservative Republican wish list.

Like Newsom’s fight against the recall, it was a grueling and bitter campaign with a reelection contest the following year.

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Though the details were different — notably, Newsom won — it was the tone in 2005 that was most remembered by political watchers. Schwarzenegger sought to cool tempers, promising “more collaboration and more working together.”

“So I got that message,” he said.

Less than a year later, after retooling his political brand — becoming less Republican and more what he called “post-partisan” — Schwarzenegger easily won a second term, beating Democrat Phil Angelides, the state treasurer, by 17 percentage points.

The 2005 setback felt personal for Schwarzenegger, and the recall effort could be similar for Newsom. Even in victory, a recall forces an incumbent to stand for an embarrassing vote of no confidence.

Here’s what we know after the polls closed about the attempt to recall Gov. Gavin Newsom.

But if Newsom is to acknowledge that his actions played some part in causing the election that ended Tuesday, he’s keeping it to himself. The furthest he seems willing to go is a promise to keep doing what he’s been doing.

“I really just want to reinforce to folks that I’m committed to finishing the job,” he told the San Francisco Chronicle last week.

While that might be enough for most voters, they may still be less than enamored with Newsom on a personal level.

The pandemic has turned one of Newsom’s signature strengths against him. His reputation as a policy wonk who loves details and data became a caricature during the drawn-out daily livestream events he held during the height of the public health crisis last year. It’s unlikely that any governor has ever asked an audience so often to “forgive the long-windedness” of his remarks, or punctuated his comments with unrelenting promises to “meet the moment” with “intentionality” while also being “iterative” and embracing an “equity lens.”

Ann O’Leary, who served as Newsom’s chief of staff until mid-December, said the online briefings seemed the best course of action at the outset of the COVID-19 crisis, recounting that a Fresno resident had contacted the governor’s office and praised his presentations, telling the staff she was a loyal Republican.

California voters overwhelmingly rejected the attempt to remove Gov. Gavin Newsom before the end of his term.

O’Leary concedes that the kudos soon faded, though she believes the frustration with Newsom was ultimately a reflection of the public’s fear.

“They wanted answers,” she said. “And nobody had them.”

Newsom, though, kept going. There was the game-show-styled event to hand out cash prizes to a few Californians who had agreed to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. And the event in June, alongside a Transformer and the movie-famous Minions, to celebrate a return to theme parks.

When Newsom was spoofed on “Saturday Night Live” in February, the cast didn’t pull any punches.

“He’s hated by every single person in California except those 10 people he had dinner with in Napa that one time,” said comedian Kate McKinnon, playing Dr. Anthony Fauci in a skit in which Newsom and other governors decided who would get in-demand doses of the COVID-19 vaccine on a game show.

Larry Elder shook up the recall campaign. What will the conservative talk radio host do next?

The Napa Valley dinner at the French Laundry, likely to be remembered as a major political blunder, fueled the recall petition. Even with Tuesday’s victory, it remains a reminder of privilege and access.

“There’s an aspect of Newsom that’s off-putting to some people,” South said. “There just is. It annoys some people, and it annoys some of my Democratic friends. But ultimately, I think voters judge California politicians on the job they do.”

Newsom, perhaps more than most governors, elicits strong feelings that may not reflect who he really is, said some of those who have worked alongside the governor and who asked not to be identified in order to speak candidly.

They believe the perception gap between Newsom the man and the sometimes ridiculed public figure is enormous — and that, if anything, he is overly introspective and a chief executive sometimes consumed with self-doubt. Newsom, they said, is a man who often sees his work and accomplishments as the glass that’s half-empty.

“Cocky is the last word I’d use to describe him,” one former aide said.

And at times, another former advisor said, the pandemic-era criticism of a governor who kept changing course was largely the result of Newsom taking actions that reflected the lack of consensus inside the administration during the early months.

By late January, the governor’s job approval rating was below 50%. Fewer than one-third of voters in a UC Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies poll co-sponsored by The Times thought he was doing a good job on the state’s coronavirus response. Even fewer voters said he was effective at balancing public health demands with the need to support the state’s ailing economy.

Some of those close to Newsom would like him to find a way to be more focused now that the recall has failed; they worry that his time as governor has been marked by his habit of taking on too much. They say the do-everything-at-once approach has fueled the frustration of other elected officials and advocates for the broader agenda of the Democratic Party.

But none of the people interviewed believed Newsom will be a different person after surviving the recall. Some believe it will be hard for the governor not to see the results as a total vindication.

There’s a political downside for an elected official who changes too much, said South, who was once the chief political strategist to former Gov. Gray Davis.

“I don’t know that they ever fundamentally change,” South said of politicians. “They are who they are. And it seems phony when you try.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.